A visit to the Gothenburg Book Fair – celebrity cultural capital and the power to speak back

2026-01-15

By: Serena Fedeli

Disclaimer: this post is intended as a recollection of personal experiences following a university seminar and two interviews which I attended. I will relate them along with some excerpts which I have noted down by hand, and which therefore should be taken for what they are: loose quotations. In what follows, you will see authors, discussions and even scholarship through my eyes.

A few weeks ago, I attended the annual Gothenburg book fair, an event which gathered almost 100 000 visitors this year. I was interested in particular in listening to two interviews with two Nigerian authors, which I wished to observe and compare. The idea came from a discussion from a seminar that I attended recently, in which the guest lecturer, dr. Doseline Kiguru, discussed African celebrity writers and canon formation, as well as the idea of ‘poverty/trauma-porn’. According to my understanding of Kiguru’s arguments, there is in fact a connection between contemporary African fields of literary production, canon formation and capital circulation which should not be overlooked. In short, Kiguru’s analysis, building on Bourdieusian notions of cultural capital, places the literary text within a framework of production, to bring forth the interlocking mechanisms that exist between cultural/literary capital value and circulation, and canon formation (see Kiguru 2016 for more on this topic). A common denominator between the two texts read to prepare for the seminar was the figure of the celebrity African writer, often a winner of prestigious literary prizes, who embodies in their public persona the accruement of social and cultural value, and therefore power, in Bourdieusian terms (see Kiguru, 2022 for the figure of the celebrity writer). Moreover, during the seminar, we had the chance to observe the features of the short stories which, throughout the years, won the Caine Prize for African Writing, finding a blatant similarity amongst them all: the common topic of poverty, trauma and sufferance. With these in mind, I headed to the Gothenburg book fair, to listen to two award-winner Nigerian writers —Chigozie Obioma and Chimamanda Adichie— and observe if and how their ‘celebrity power’, so to speak, played out in the interviews. The experience did not disappoint.

Figure 1: The large crowd at the Gothenburg Book Fair 2025

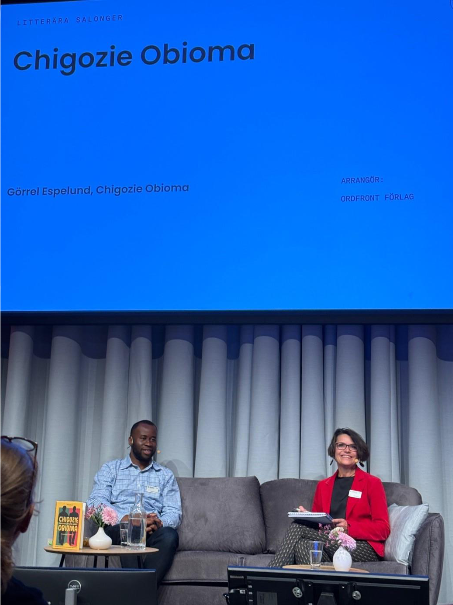

The first interview I attended was with Chigozie Obioma, about— supposedly— his latest novel The Road to the Country, which, admittedly, I am yet to read (I will!). I hope Obioma will not get offended if I state that he is not quite the same celebrity as Chimamanda Adichie, though her popularity is truly hard to beat, but more on that later. Even though his words might not have been associated with fashion shows and Hollywood stars like Adichie’s, Obioma is still a well-established writer, with a bunch of prestigious achievements under his belt. In 2015 alone he was named one of the ‘100 global thinkers’ by Foreign Policy magazine and called ‘the heir to Chinua Achebe’ by The New York Times, which is, arguably, quite impressive. Moreover, he served as a judge for the Booker Prize, and he is a distinguished professor of English at the university of Georgia, which, to me, means that he knows a thing or two. Nonetheless, the Gothenburg book fair did not consider that he would gather such a crowd, and in fact the interview took place in a rather small room.

Figure 2: Chigozie Obioma

Interestingly, the interviewer (a journalist) set the tone for the whole conversation right from the first moment, contextualising the novel in the period of the Biafra war. A large chunk of the time was subsequently dedicated to asking the author about the formation of the Nigerian nation state, colonialism, and the arrival of the British. Despite this speedy lesson on colonial history, the interviewer at this point said again: “Though, really, the war is the centrepiece of the novel”. Obioma explained then that he believed some of the best stories to be those that deal with “a rebel without a cause, fighting against his own convictions”, and proceeded to illustrate what he saw as the most interesting features of his novel: the inner development of the main character, the deep bond he formed with the other soldiers, “the genuine attention and love for others”, “war as a refining tool for human identity”… in other words, showing that war is not to be monumentalised, and that such a tendency is part of a larger “Enlightenment project”. Yet, monumentalising is precisely what I understood the interviewer to be aiming at. At this point in fact, an interesting back-and-forth dynamic surfaced between interviewer and interviewed. On the one hand, the journalist who time and time again went back to real-life issues of war and trauma, such as the author’s research on the Biafra war, his meetings with veterans: “how much of it is based on real events?”. On the other, Obioma talking about African literature, the importance of the mystical in today’s life, and his attempt to “offer the metaphysical to open up questions in the reader’s mind”, insisting that veterans do not really talk much about the war. This exchange, which in the end was centred around real-life war, resulted in the author exclaiming: “I know you are all very pragmatic and rational, this is Sweden after all!”. Ok, I said to myself, should I take this as frustration? Nevertheless, this talk was all about the ‘trauma-porn’ we discussed with Kiguru, and I wondered if that could be due to the fact that the author did not embody enough power in his celebrity personhood to simply speak about whatever he wanted: cosmology, mysticism, identity, solidarity…cool stuff! Instead, he ended up feeding his Swedish audience a generous portion of trauma and sufferance so dear to the sympathetic Western reader. Admittedly, I was a bit frustrated by the predictable outcome, somewhat ashamed to embody the stereotypical Western reader myself and still rather curious to hear what the author could have said about his writing, if only he had been given the opportunity. Let’s move on.

Next on my program was nothing less than celebrity-superstar writer Chimamanda Adichie. The Gothenburg book fair had organised her seminar in the biggest room they had, which holds 500 people. To give you an idea, after queuing for 45 minutes I got nervous that I would not manage to get in! If you are not familiar with Adichie (aren’t you though?!), she is exceptionally famous, she won more prizes than I can list here, she spoke with Michelle Obama, Kamala Harris, Robert De Niro among many others, she collaborated with Beyoncé, Dua Lipa and the Met Gala designers, her Ted Talk words were printed on Dior’s clothes …in short, celebrity capital through the roof. I must admit, I was not immune to her charm, this became clear to me right away. I even forgave her for arriving almost 40 minutes late, in true celebrity style. I liked her right away, when she said that the first thing she thinks about when she finds out that she has won an award, is what she is going to wear; this small detail, I thought, served the purpose of instantly connecting her to her audience: she is one of us in some ways, but with an added wow-factor that makes her different from us…she has a stylist, after all!

This talk was surprising. Adichie received the 2025 Mermaid Award, and was interviewed during the ceremony by author Agri Ismaïl. The dynamic between the two was very different than in Obioma’s interview, not because of the interviewer, I would say, but because Adichie stirred the conversation from the beginning. In fact, Ismaïl started by talking of Adichie’s supposed postcolonial identity, but she replied that she is “not nostalgic of pre-colonial West Africa”, and when asked about her intention to move from a postcolonial to a post-postcolonial narrative she asserted that the African writer always gets asked about postcolonialism, but she wants to talk about those same “universal feelings that drive Western classics”, insisting that formerly colonized people do not think of themselves as postcolonial subjects all the time and —drum roll— that people read novels from the global south as anthropology, while literature is universally human; therefore, she does not want “to see her characters framed as representatives of Nigeria’s postcolonial identity”. At this point, Ismaïl was literally forced to change the trajectory of his interview (which he did, with a few bumps, rather well).

Figure 3: Chimamanda Adichie receiving the Mermaid Award

It was really clear to me as a spectator that Adichie from this point on stirred the conversation towards what she wanted to talk about: the evolution of her characters, her relationship to them and how this relationship registers in the narrative’s form in terms of first- or third-person narration, for example. Nonetheless, the speaker tried again to discuss some more ‘postcolonialism’ and brought up literary historian and critic Franco Moretti and the idea of the novel as the prime cultural artifact of the European Bourgeoisie. He asked: “doesn’t the form itself force you to conform to something that doesn’t really represent non-Western realities?”. To which Adichie replied that “the novel has become African because Africans have written it” and reiterated, once again, that belonging to a formerly colonized country should not define everything that the African writer does, including when it comes to the use of the English language: “Igbo is mine and English is also mine. Can we just move on?!”. Towards the end of the interview, the conversation acquired a somewhat political tone, as Ismaïl asked Adichie for some advice to those in the U.S, “living their first dictatorship”. According to Adichie, who has herself been living in the U.S for decades, people in America should remember that their country has a long history of imposing dictatorships to others, so they should “suck it up”. The end, long applause. Wow, I was truly mesmerized not only by her words, but also by her wittiness and audacity, her presence and power.

Figure 4: Chimamanda Adichie signing my copy of her latest book

To sum up my considerations of this experience then, I think that not only do we, Western readers, still seem to have a very soft spot for ‘poverty-porn’, a need to feel sympathetic towards the so-called Global South, even when it comes to fictional representations of it; that this, in simple words, is still what sells. But also, I got to observe the very evident connection between celebrity status and ‘power’, and how the writer who has been canonized through recognitions and international literary awards, accrues enough symbolic and economic power that can be used to support and/oroppose other matters and causes which depart from the literary industry and expand to larger cultural, social and political issues. Essentially, the subaltern can speak, in Spivak’s words, but only when she is a superstar.

Further readings

Kiguru, Doseline. 2016. “Literary Prizes, Writers’ Organisations and Canon Formation in Africa”, African Studies 75:2, pp. 202–214.

Kiguru, Doseline. 2022. “Contemporary African literature and celebrity capital”, in African Literatures as World Literature, edited by: Alexander Fyfe & Krishnan Madhu, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 189–211.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2001. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Imperialism, edited by Mark Harrison and Peter J. Cain, 171–219. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Recent Comments