A Refugee – Displacement through the Lense of Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

Postat den 15th January, 2026, 09:28 av karubakeeb

By: Serena Fedeli

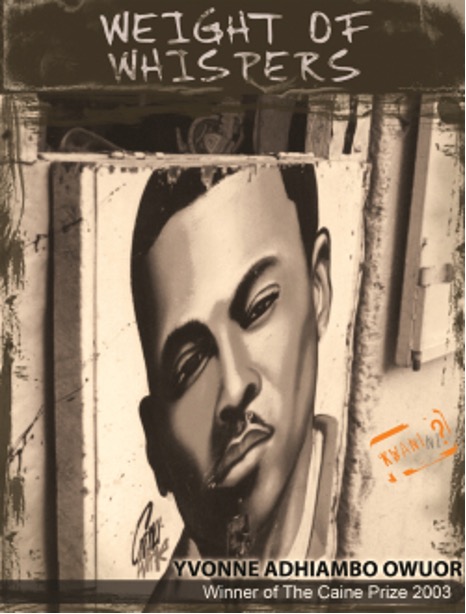

“Weights of Whispers” is a short story by Kenyan author Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor which won the prestigious Caine Prize for African writing in 2003. It is a short story that feels, well… long: it is slow, complex and intense. The first time I read it, these features confused me: shouldn’t a short story be immediate and, I guess, short? Moreover, I thought, can one really describe the experience of genocide in a short, limited space? It is, however, the story’s intricate complexity that captivates the reader and makes it impossible to let go of it. In what follows, I wish to highlight some of the ways in which Owuor’s skilful writing delivers the convoluted and multifarious experience of genocide in a brief novella, guiding the reader into, somehow, making sense of it. This story is set in Kenya and follows the experience of displacement and decline of Rwandan prince Boniface Louis R. Kuseremane and his aristocratic family, following the Rwandan genocide and their consequent exile to Nairobi: “The sum total of what resides in a very tall man who used to be a prince in a land eviscerated” (2). While it fictionalises a real event, the story is able to make it believable, I would argue, by approaching genocide from the perspective of the individual, and by narrating it in first person; that is, this story brings the reader close to the experiential level: it guides the reader into feeling a genocide, rather than just simply learning about it.

It all begins as Kuseramane and his family are forced to escape Rwanda following the assassination of two presidents, for which Kuseremane ends, somehow, on a “ a list of génocidaires” (14). Along with his fiancé, mother and sister, he flees to Kenya with their belongings stuffed in exclusive Chanel suitcases, on four of “the last eight seats on the last flight out of [their] city. [They] assumed then, it was only right that it be so” (5), as if they deserved those seats somehow, given their status. In Nairobi, they check into a suite at the Hilton. Money is running low, both Kuseremane and the reader are well aware of it. It becomes clear to him that they will not be able to sustain their exclusive lifestyle for much longer. They are ultimately forced to flee the hotel in secret, aristocrats turned common thieves, without paying their bills; they leave the Chanel bags behind at least, since “they are good for at least US $1500. Agnethe-mama is sure the hotel will understand” (13). From that point on, life takes a very unfamiliar turn; it takes a while, for Kuseremane —the prince— to understand his new status, for, he states, “The Kuseremanes are not refugees. They are visitors, tourists, people in transit, universal citizens with an affinity…well…to Europe” (9). However, he will soon find out, to seek asylum is not to be a citizen of the world, it is, actually, to go from being a someone, to becoming dehumanised, all the same, a mass of people with no country and no name: “all eyes, hands and mouths, grasping and feeding off graciousness” (14). In one of the very many queues for visas and permits which he is forced to join, Kuseremane observes “Like the eminent-looking man in a pin-striped suit, I am now a beggar” (12), the fact that he is a diplomat and a prince is totally irrelevant. The visa application process proves to be literally impossible, for it must be done in one’s own country, and Kuseremane’s country is…well, even Kuseremane himself does not know what is left of his country at this point (11). He spirals more and more into anguish and fear, unsure of whether to give up or resist; he becomes too afraid to voice his terror to his family: “it is simpler to be silent” (9), to believe that the tears that wet his pillow in the morning are not his (13). Who is he, anyways? “Kuseremane, Kuseremane, Kuseremane” (13) he repeats, more for the sake of reminding himself than anything else, for nobody around him seems to remember him, even though they knew him well when he was a someone. He could be an “expatriate’ and therefore desirable” (27) back then, while now he is an “illegal alien” (24), a “pariah” (27) in exile, a nobody, whose humanity is rapidly fading before his very eyes. In his new condition, his identity needs to be suppressed: “Camouflage… place dictates form. […] The first lesson of exile – camouflage. When is a log…not a log? When a name is not a name” (30-31).

Owuor is skilfully able to draw parallels between the character of Kuseremane and the figure of the Jew, without, however, universalising this experience in a way that would risk further degrading of the human behind it. In other words, the author uses the idea of the Jew as a trope, to challenge the reader’s ethical standpoint. Through Kuseremane we are uncomfortably reminded, once again, that “the zenith of existence cannot be human” (Owuor, 3), for “nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings” (Arendt, 111) with no rights left but human rights, as Hanna Arendt once wrote in her well-known text “We Refugees”. Arendt writes that to be a refugee is to be stripped of all humanity, but what are human rights good for, when humanity fails to see you as a human? Refugees do not want to be called ‘refugees’, they do all they can to prove themselves and others that they are “just ordinary immigrants” (110). Refugees, according to Arendt, have not only lost their home; they lost their language, their jobs, and their identity is now dismembered (110).

Kuseremane, the refugee prince—the genocidal prince perhaps— is not a Jew, yet he is not spared from this condition. However, the reader’s ethics are challenged here: we are unsure whether to see him as ‘the Jew’ or ‘the Nazi’, as some scattered textual elements reveal. His lack of tact and human empathy in meeting an academic whom he asks, bluntly, “are you a Jew?”, causing the man to cry, then simply walking away “unable to tolerate the tears of another man” (3). Moreover, Kuseremane is often depicted wearing a Hugo Boss coat (15), a designer notably known for having made his fortune by creating uniforms for the Nazi government in the 1930s. In this way, “Weight of Whispers” arguably succeeds in making an ethical intervention; that is, Owuor uses tropes such as these historical references to place the reader in relation to the subject it engages with; not only in making us understand genocide from an experiential level, but also urging us to take an ethical stand, questioning ourselves, and in so doing making sense of things from an ethical perspective as well. The whole idea of Nazi Germany is, thus, encapsulated and crystallized in a Hugo Boss suit. Even those who might struggle with historical references (those for whom ‘the past is another country’, as someone once said), are given the opportunity to question their ethical point of view through, for instance, the questionable role of the UNHCR in Kuseremane’s process of asylum seeking. Indeed, what are human rights good for, when even the UN office for the protection of refugees requires a 200$ bribe to decide who gets to enter their offices? (22) And even then, when leaving depends on whether or not you are willing to ‘cooperate’, “by agreeing to be examined […] by the officials at their homes for a night.” (34)? Kuseramane is powerless, he can do nothing but watch (35).

The story’s ambiguous end left me wondering if its protagonist will end up committing suicide —the ultimate identity erasure—again, echoing Arendt (112-113). But, much more importantly, the story ends leaving me uneasy, having to grapple with the experience of exile. Thus, this is not just a matter of first-person narrative. It is about the much larger question of first-person engagement in the real-life displacement of millions of people. This story demands that we —you and I— remember that according to the UNHCR’s latest report there are over 122 million forcibly displaced people in the world, real people, that is. Perhaps Owuor would argue that very many more might never reach the UNHCR at all. Albeit fictional, this story shakes our moral grounds, and urges us to keep seeing the human behind the figure of the Refugee. “Photographer, do you see us at all?” (Owuor, 32).

Further reading:

Arendt, Hanna. “We Refugees”. Altogether Elsewhere: Writers in Exile. edited by Marc Robinson. Faber and Faber, 1994, pp. 110-19. Originally published in 1943.

Owuor , Yvonne Adhiambo. “Weight of Whispers”. Nairobi. Kwani Trust, 2003

UNHCR. “Press Releases, 12 June 2025. https://www.unhcr.org/news/press-releases/number-people-uprooted-war-shocking-decade-high-levels-unhcr

Wikipedia. “Hugo Boss”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugo_Boss

Det här inlägget postades den January 15th, 2026, 09:28 och fylls under blogg