Caught Within the Gaps of Standardised English in Xiaolu Guo’s A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers

Postat den 13th May, 2025, 19:22 av karubakeeb

By Hanna Järvbäck

Is There a Language Out There, for You and I to Share?

Could there ever be a moment,

In which their eyes could lock,

Their thoughts intertwine,

And their tongues roll in the same motion?

Will there ever be a moment,

When he understands the weight –

Of her hmms… and her aahs…

The heaviness she carries in her extra seconds of consideration?

Is there ever going to be a moment,

Where he will take the time –

Patiently and non-defensive,

To genuinely listen?

Can there ever be a moment,

When our languages meet?

Poem by: Hanna Järvbäck

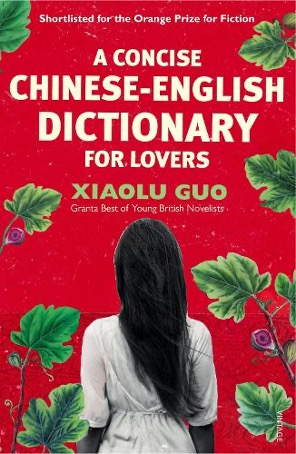

Can communication transcend the boundaries of language? Or, perhaps, more distinctly, how can we ensure that voices that struggle while veering away from their mother tongue are genuinely heard? My poem ‘Is There a Language Out There, for You and I to Share?’ is inspired by my numerous re-readings of Xiaolu Guo’s novel A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers. Guo’s novel critiques the circulation of imperial knowledge and exposes the power imbalances between native “Queen’s English” speakers and English language learners. In the poem, I have aimed to echo the struggles experienced by protagonist Zhuang to be understood while navigating a foreign linguistic and cultural system.

A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers follows the tale of Chinese student, Zhuang, arriving in London to attend English language school. Written as a multimedia non-alphabetical dictionary/diary, the novel opens with a broken English first-person narration. However, as the story unfolds, the reader gets to follow Zhuang’s journey of developing more English language skills (as shown in her writing) as she engages in an intimate relationship with “You” – an older English man – who becomes her adviser and dependant in the foreign country. As her English language skills improve, their relationship deteriorates as cultural ignorance, misunderstandings, and assimilation ideals become more enhanced and pronounced. Zhuang’s journey to learning the “Queen’s English” is far from easy, and she often feels at a loss towards its linguistic power, which differs significantly from her native Mandarin. Having to continuously code-switch and translate between languages in conversations with “You” causes Zhuang to question her identity and purpose in the West. While asking how to be herself in a second language and how to make herself genuinely understood, Zhuang eventually, in a hauntingly reflection, admits:

I am sick of speaking English like this. I am sick of writing English like this. I feel as if I am being tied up, as if I am living in a prison. I am scared that I have become a person who is always very aware of talking, speaking, and I have become a person without confidence, because I can’t be me. I have become so small, so tiny, while the English culture surrounding me becomes enormous. (180)

Guo leaves the reader contemplating how language is intrinsically intertwined with identity, as the desire to be understood transcends the grammatical boundaries of imperial Standardised English.

In my latest re-read of A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers, I paired it alongside Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Woman, Native, Other, which explores how imperial literary discourse positions women writers of colour in a “triple bind” of racial and sexual prejudices, anchored in the ‘white- male-is-norm ideology,’ a framework Minh-ha describes as ‘used predominantly as a vehicle to circulate established power relations’ (6). Circulating in a sphere of continuous politicisation of her ethnicity, gender and choice of profession, the woman writer of colour ‘must learn to paint her world with colors chosen often by men for men to suit their realities’ (27). This pairing added a new layer of appreciation and offered a powerful lens through which to view Guo’s work. The reader can, from the beginning of the novel, detect a resistance towards the “white-male-is-norm ideology”, through reflections such as: ‘English a sexist language. In Chinese no ‘gender definitions in sentence … Always talking about mans, no womans’ (26). However, Guo’s interrogation of this Eurocentric ideology shines through in the unfolding of Zhuang’s relationship with her lover. While in a conflict on the “correct” way to speak, act and live, Zhuang slowly but surely begins to challenge her lover’s sense of entitlement, suggesting: ‘Your happiness is from your masculine world, and in that world you feel everything is under the control. Your sadness actually is nothing to do with me. Your stress is not really from me’ (192). In this reflection, Zhuang resists engaging with her lover’s view of reality. This becomes a theme that Guo applies throughout the novel, illustrating how imperial power imbalances can infiltrate intimate relationships, revealing the emotional toll on the one positioned as socially and culturally inferior.

So, can we ever escape this circulation of power dynamics? Minh-ha considers that there are bound to be cracks within every system, and within language constructions, there are ‘blanks, lapses, and silences that settle in like gaps of fresh air as soon as the inked space smells stuffy’ (19). I encountered Guo’s novel in my first year as a Swedish international student at University of Brighton, when my self-esteem regarding my language abilities was at its lowest. Although my positionality differs significantly from the main character (and here, we need to take time to underline the privilege that I possess, which Zhuang does not – as a white Westerner), I felt a connection to her frustrations. I had moments when language felt like a heavy backpack dragging me down; however, taking it off would feel worse because I feared I would stand empty-handed without it. Through the narration of Zhuang, Guo consistently takes the readers into the gaps of standardised imperial English and shows them the identity and voice that flow in the spaces between its constructions.

Now, my copy of the novel is withered and weathered – notes scribbled all over and coffee stains splattered on some pages – from all my re-reads. To say that I have simply loved this book would be an understatement. Guo’s novel reminds us that language is never natural – it has the power to construct how one sees oneself in society. Nevertheless, perhaps more remarkably, the novel shows how a marginalised voice can seize agency. I warmly recommend A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers to everyone interested in how language shapes identity and belonging. And I hope it will inspire you, as much as it did me, creatively or reflectively.

REFERENCES

Guo, Xiaolu. A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers. Vintage, 2007.

Minh-ha, Trinh T. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Indiana University Press, 1989.

Det här inlägget postades den May 13th, 2025, 19:22 och fylls under blogg