Saints and Holy Wells – A Medieval Tradition?

2021-02-23

Terese Zachrisson, University of Gothenburg

St. Olaf’s Spring and ”St. Olaf’s Cauldron” in Borgsjö, Medelpad.

Bodies of water believed to be gateways to the supernatural are a common aspect in many cultures, and they are still a feature of modern Christianity. The veneration of springs is an adaptable tradition that can be tied to deities, saints and other supernatural forces, all according to the particular cultural context in which they are found. In medieval Europe, many wells and springs were associated with the saints. Healing miracles frequently occurred at these wells, and pilgrims left votive offerings at the sites. At times, the crutches and canes left behind would pile up by the wells, as a testament to the intervention of the saints.

In the Swedish source material, holy wells and springs are frequently mentioned in 17th-century antiquarian reports, where they are usually described as remnants of a ‘superstitious’ Catholic past. Some of the springs were dedicated to universal saints, such as the Virgin Mary, St. Lawrence or St. Nicholas, but a large portion of them were connected to regional and local saints that were believed to actually have been present at the sites during their lifetimes. St. Olaf and St. Sigfrid, who according to tradition travelled extensively during their lives, have both left a particular abundance of footprints in the form of natural objects bearing their names. But holy wells also give us glimpses of saints’ cults that are otherwise largely unknown — for instance St. Ingemo in Dala, St. Torsten in Bjurum, and St. Björn in Klockrike.

But can we really know that holy wells and the religious traditions associated with them were part of medieval lived religion, when the majority of the sources are from the early modern period? The answer is that we simply cannot know for sure, but that there is a high probability that they were. Holy wells have been strangely neglected in modern Scandinavian research. When mentioned at all, they are often, especially in popular publications, sweepingly referred to as ‘pagan survivals’. There has been some scholarly debate in Denmark as to their status in the medieval tradition. Jens Christian Johansen (1997) and Susanne Andersen (1985) both state that holy wells are to be viewed as a primarily Post-Reformation phenomenon, and that evidence of the cult is almost entirely lacking from the medieval period. According to this view, the cult of holy wells developed in the early modern era in part as a way of compensating for the loss of the saints in institutionalized religion, and in part due to the growing fashion among the upper classes of attending spas and mineral wells.

That the Reformation and the sudden disappearance of several previously important channels to the divine led to a surge in visits to holy wells and other sites that were outside of ecclesiastical control is not in doubt here. But does that mean the cult of holy wells was non-existent in the Middle Ages? I would argue not. While evidence of the medieval cult of holy wells in Sweden is unusual, it is not entirely lacking.

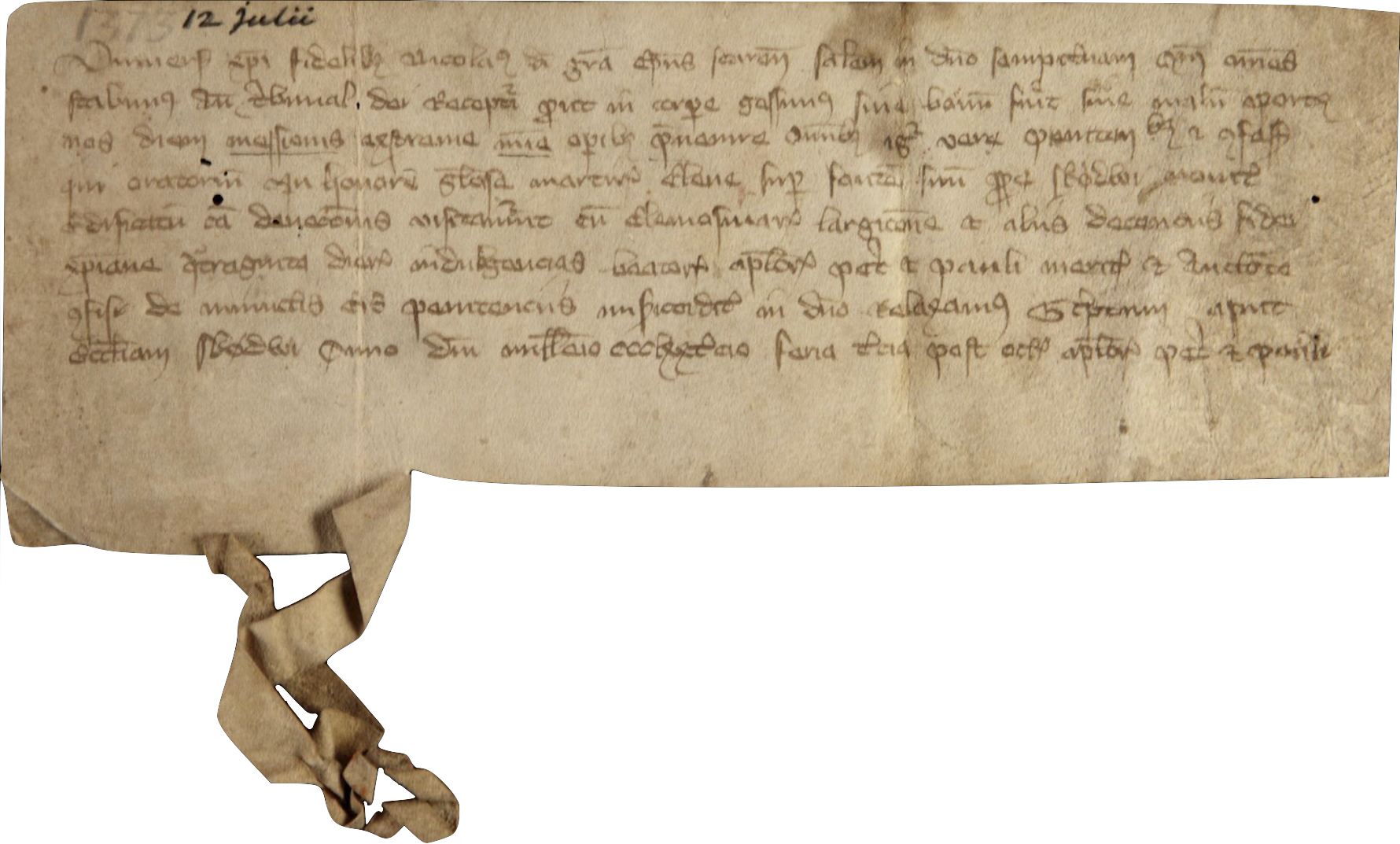

Letter of indulgence for the chapel above St. Elin’s Spring in Skövde, Västergötland.

Photograph by the Swedish National Archives.

The most prominent examples are the two springs dedicated to St. Elin of Skövde in Skövde and Götene in the Skara Diocese. Already in the officium to St. Elin composed by Bishop Brynolf Algotsson (in office from 1278–1317), it is mentioned that a spring miraculously appeared at the site of Elin’s martyrdom. In addition to this, we have three preserved letters of indulgence that mention the sacred springs. In a letter from 1373 (SDHK 10386), Bishop Nils of Skara grants 40 days of indulgence to pious visitors to the oratorium jn honorem gloriose martiris Elene super fontem suum prope Skødw, that is, “the shrine in honour of the glorious martyr Elin, above her spring near Skövde”. Though the indulgence primarily concerns the shrine or chapel built above the spring, the spring itself seems central: on the back of the letter, a later scribe in a 15th-century hand, has added the words: indulgencie ad fontem — indulgence for the spring. The indulgences granted at the Skövde spring were reaffirmed in another letter in 1425 by Bishop Sigge (SDHK 20587). The other St. Elin’s Spring, at the site of her murder in Götene, is also mentioned in a letter of indulgence, issued in 1462 by Bishop Lars of Växjö (SDHK 40914). In this letter, indulgence is granted to those that under certain conditions visit Götene Parish Church, but also to those that with good intentions visit the Fontem Sancte Helene.

Some legal sources also mention holy wells. In the court records from the town of Arboga in 1459, Hælge Swens kællo — a holy well dedicated to the elusive local saint Sven of Arboga — is mentioned briefly. The most famous holy well in Sweden was likely Helga Kors källa (‘Holy Cross Spring’) in Svinnegarn parish in the archdiocese of Uppsala. Accounts of the cult of this spring are abundant from the early modern period, but the cult is alluded to in sources that strengthen its ties back to the Middle Ages. In 1487, a man in Stockholm convicted of manslaughter was required to make several pilgrimages in order to atone for his crime, with one of the locations being Svinnegarn. In his 1566 writing on church ordinances and ceremonies, Reformer and first Lutheran Archbishop Laurentius Petri stated his disapproval of how the ‘popish’ clergy had consecrated wells and springs. In the same work, he also criticized the previously abundant pilgrimages to famous sites like Rome, Santiago de Compostela – and Svinnegarn. To be fair, we do not know whether these sources refer to the church of Svinnegarn, the spring, or indeed both. That the spring itself had been the object of pilgrimage is indicated by the writings of Johannes Messenius (1579–1636). According to his Scondia Illustrata, a holy crucifix had been placed at the renowned Svinnegarn spring, and it had been removed by Laurentius Petri. Messenius lived in close proximity in time to the later part of the Swedish Reformation, and many in his audience could easily have falsified his claims were they not common knowledge at the time. Several coins have also been located in the spring, though the oldest one is dated to the 1590s — but the offertory log that according to oral tradition used to be placed by the spring, contained several coins from the period 1275–1520.

Medieval comb found in one of Barnabrunnarna in Tolg, Småland.

Photograph by the Swedish National Heritage Board.

Speaking of archaeological finds, in 1901, when clearing one of the Barnabrunnarna (literally ”Children’s Wells”) in Tolg parish in Växjö Diocese, nearly 6000 coins, tokens, and other small objects were found. The majority of these offerings could be dated to the period between the late 16th century and the mid-19th century, but among them were also a medieval comb and a coin issued in the reign of King Magnus Eriksson (1319–1354). That so few medieval objects have been found in holy wells could either indicate that the cult was only a minor feature of medieval lived religion, or that many of the springs were cleared at some point following the Reformation. But whether the cult was a major or minor aspect of the medieval repertoire of piety, it certainly did occur.

There is also the aspect of the place of Scandinavian religious culture in the context of a wider medieval Christendom. Recent research has demonstrated that Scandinavian Christianity was firmly in line with the church in Rome, with a vast and active network of ecclesiastical communication, and by no means as ‘peripheral’ as previously believed. The cult of holy wells was an integrated part of everyday piety throughout Christian Europe – why would Scandinavia differ from the rest in this particular aspect? Concluding that since records of the Scandinavian cult of holy wells in the Middle Ages are scarce, it did not exist, is an argumentum ex silentio. But at the end of the day, every scholar using our database will have to make their own assessment of the evidence available.

Further reading:

Celeste Ray (ed.), Sacred Waters: A Cross-Cultural Compendium of Hallowed Springs and Holy Wells, Abington 2020.

Alexandra Walsham, The Reformation of the Landscape: Religion, Identity, and Memory in Early Modern Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2011.

Terese Zachrisson, Mellan fromhet och vidskepelse: Materialitet och religiositet i det efterreformatoriska Sverige, Göteborg 2017.

Recent Comments