Vilma Mättö, Linnaeus University and University of Turku

In my previous blog-post, I introduced the major painting series that are preserved in Finnish medieval churches and listed some of their key features, namely the overlays and fragmentation caused by various factors. In this blog-post, I will discuss a few specific cases to exemplify how these features should be taken into account when analyzing the depictions of saints.

The fragmented nature of the material poses challenges. Each wall painting exists in relation to other images, formulating chronological or thematic entities, and associations with one another. The interpretation of the whole iconographical program gets more complicated when the material has been somehow altered or damaged (Aho 2023, 20). This can also hinder us from identifying individual motifs. For instance, in many cases it is hard to determine what saint a figure represents or even to recognize if a depicted person is a saint in the first place.

Sometimes, even though the actual image is mainly intact, but the identity of the portrayed person is still uncertain. The identification of a saint is made firstly with the help of related attributes. However, the attributes connected to each saint have varied depending on the area where the saint was venerated (Nygren 1945, 15–18). It is also evident that painters visualized saints in their own creative way and sometimes they might have confused saints with each other or simply made a mistake and connected a saint with the wrong symbols.

Fig 4. Painting of St Christina in the church of Hattula. Photo by Janika Aho.

Because we lack contemporary written sources that describe and explain the content of the church murals – let alone the intentions of their makers – other pictorial reference material is a crucial aid in identifying the saints featured. For example, in Hattula church, St Christina of Bolsena is depicted with a knife, which is not her usual attribute (Fig. 4). Even so, the identity of this female saint is easily unraveled, since the closest comparable example in Lohja church shows Christina with another edged weapon, a small sword, and a more common attribute of hers, the millstone.

Fig 5. A pelican feeding its young with blood, symbolizing the sacrifice of Jesus, and depiction of St Christina of Bolsena at the lower right corner. Photo by Janika Aho.

Some other good examples of the importance of comparative material are the paintings representing St Botolph of Thorney in the churches of Lohja (Fig. 6) and Hattula (Fig. 7). In Lohja, the east wall of the chancel shows a depiction of a bishop with a crozier and a mitre in his right hand. In earlier research, this saint has been interpreted as St Dionysius based on the assumption that the painting had later been restored incorrectly, and that the mitre in his hand was in fact an erroneous version of the Dionysius’ decapitated head (Nygren 1945, 102–105). In Hattula, the depiction of this saint is quite similar to the painting in Lohja, showing the saint in a bishop’s cope and with a mitre and crozier in his hands.

Fig 6. An unknown bishop, possibly St Botolph, depicted in the church of Lohja. Photo by Janika Aho.

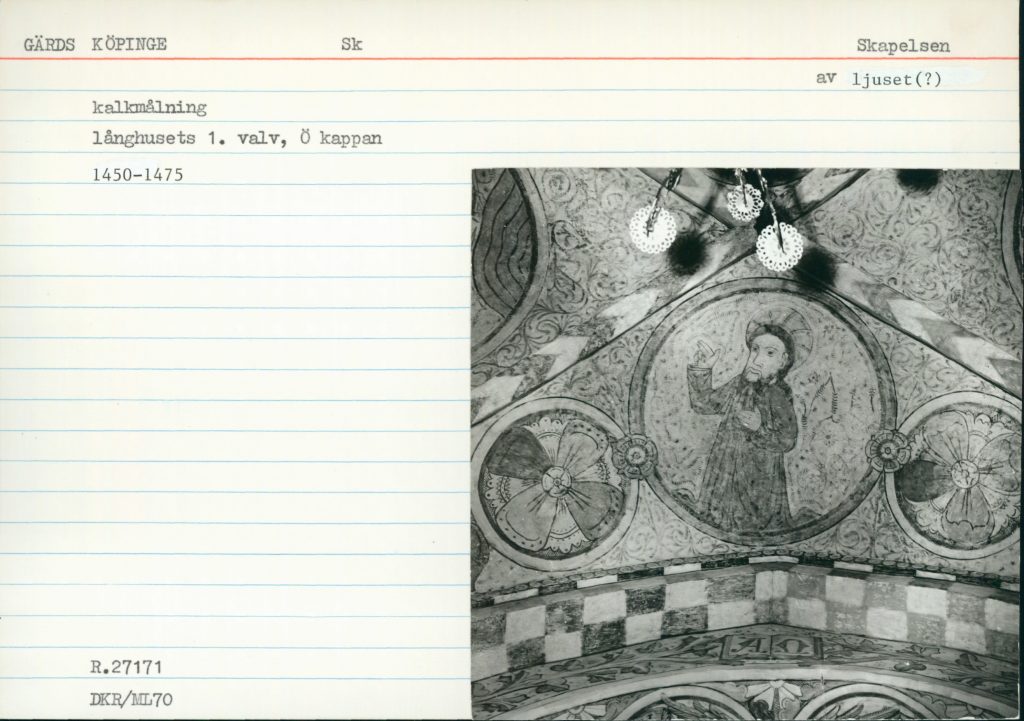

Later, art historian Anna Nilsén compared the paintings in Lohja and Hattula with the pictorial program of the Täby church in Sweden and noticed a resemblance between some of the motifs. In Täby church, St Botolph is correctly depicted wearing an abbot’s attire, but like in Lohja and Hattula, the mitre is with him next to his left shoulder. St Botolph of Thorney was indeed a well-known English abbot and a missionary in the seventh century (https://saints.dh.gu.se/person/45). But because the saint was occasionally informally referred to as a missionary bishop, he was sometimes depicted with a mitre and a crozier. As Nilsén has proposed, it is feasible that the painter was unfamiliar with the legend of St Botolph and therefore concluded that a saint portrayed with a mitre must have worn the cope as well (Nilsén 1986, 196, 203).

Fig 7. St Botolph? A painting in the church of Hattula. Photo by Janika Aho.

Images of saints whose identity is uncertain or unknown are included in the Mapping Saints database along with all possible alternatives that the saint in question could represent. As noted above, the identity of a saint is sometimes possible to trace by finding parallel images, such as plausible models that the painter might have used. In fact, a common method is to examine the depicted figure’s posture, gestures, accessories, and other objects connected to the person, as well as observe the style and colour of the garment that the person is wearing. In addition, a pivotal step is to contextualize the image to determine how it relates to contemporary events and actions connected to the painting’s place of origin (Vuola et al. 2018, 59–64).

The Mapping Saints database facilitates this contextualization (about the context of the artwork see, for example, Räsänen 2009, 23–24). The user can quickly form an overall picture of how the chosen images could be connected to other objects, places, people, oral traditions, texts, feast days, etc. and for example, limit the search results to a selected time-period or region. Images like wall-paintings can be treated as objects that echo the phenomena of the past. But they can also be considered as subjects in themselves, in which case the context is rather built up around the image. Nonetheless, church paintings are not only products of their own time, but they also have their own autonomous rhetoric that is continually constructing our current culture (Liepe 2003, 415–417, 424–425).

Fig 8. Painting of St Botolph in the church of Täby, Sweden. Photo from the Iconographic Index card, courtesy of the Swedish National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet).

By linking the digitized cards of the Swedish Iconographic Index (Sw. Ikonografiska registret) and re-digitized photographs of the World of Medieval Images project (Sw. Medeltidens bildvärld), the database provides a vast collection of visual data, and together with other material content and textual sources they constitute a good base for elaborating on medieval church art (see more Liepe & Ellis Nilsson 2021, 55–60). The Iconographic Index of Finland housed by the Finnish Heritage Agency has also been newly digitized and after its publication in the Finna portal will soon be complementing the database. Additionally, more photographs of the Finnish medieval wall-paintings will be published on another platform and, in time, also be made accessible via the Mapping Saints interface. The existing church murals being a fractured material overall brings its own challenges, yet they have a lot of research potential. Indeed, the Mapping Saints research resource compiles several kinds of scattered information that can bolster iconographical surveys and give support in interpretative problems, offering new possibilities and perspectives for the further study of church murals.

References

Aho, Janika. “Fragmentaarisuus Suomen keskiaikaisissa kirkkomaalauksissa: kolme esimerkkitapausta”, Suomen Museo – Finskt Museum, (2023), 19–40. https://journal.fi/suomenmuseo/issue/view/9079

Liepe, Lena, & Ellis Nilsson, Sara. “Medieval Iconography in the Digital Age: Creating a Database of the Cult of Saints in Medieval Sweden and Finland”. ICO Iconographisk Post. Nordisk tidskrift för bildtolkning – Nordic Review of Iconography, (2021), 45–63. http://ojs.abo.fi/ojs/index.php/ico/article/view/1745

Liepe, Lena. ”On the Epistemology of Images” ‒ in History and Images. Towards a New Iconology, Axel Bolvig & Phillip Lindley (eds.). Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.

Nilsén, Anna. Program och funktion i senmedeltida kalkmåleri. Kyrkmålningar i Mälarlandskapen och Finland 1400‒1534. [Stockholm]: Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, 1986.

Nygren, Olga Alice. Helgonen i Finlands medeltidskonst. En ikonografisk studie. Diss. SMYA, FFT XLVI:1. Helsingfors: SMY, FF, 1945.

Räsänen, Elina. Ruumiillinen esine, materiaalinen suku : tutkimus Pyhä Anna itse kolmantena -aiheisista keskiajan puuveistoksista Suomessa. Helsinki: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, 2009.

Vuola, K., Reijonen, H., Kaasalainen, T., & Saat, R. “Medieval Wood Sculpture of an Unknown Saint from Nousiainen: from Materials to Meaning”, Mirator, 19 (2018), 43–66.

Recent Comments