The Chinese Reform Process in a European Perspective

August 6, 2014

Paper for the SNEE Conference in Mölle / Sweden, May 20-23, 2014

Abstract

During the Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in November 2013, China’s political leadership implemented a relatively far-reaching reform program, covering many economic, social and political areas. On paper, the Chinese reform plans appear to be very progressive yet at the same time there are many conflicts of goals inherent in these policy strategies. Finding appropriate preferences for these different conflicts of goals will be difficult.

This introductory description of the paper leads us directly to the need for interdisciplinary research. In this paper an attempt is made to give the most important reform areas a natural interdisciplinary nexus. The objective is to show that China’s economic future cannot be analyzed and predicted without broader analytical tools. It is not mainly an issue of numerical long-term GDP forecasts.

Forecasts about the Chinese economy should focus more on the understanding of the Chinese political, social and the economic system rather than quantitative research. In order to gather some empirical evidence, a survey has been prepared with members of our (LNU’s) China Survey Panel. Hopefully, statistical quality and transparency will be improved during this ongoing reform process in order to stimulate a gradual improvement in the statistical conditions for quantitative analysis.

Some of the main reform challenges are exemplified by the further deregulation of the Chinese financial sector. The academic issue of sequencing seems to be particularly complicated when applied in real life. Can China learn from the Swedish financial deregulation process – and its failures?

There is no doubt that the outcome of the Chinese reform process will also be of great importance for the European (global) corporate sector. There is every reason for Europe, the U.S., and many other countries, organizations, and corporations to optimize their future cooperation with China in line with its necessary and implemented reforms. In other words: Europe (and the U.S.) should be very interested in contributing to a successful Chinese reform process as much as possible and whenever appropriate. Major Chinese reform disappointments would be scary since the European and American economies would not be prepared for such a reversal. This is a mostly forgotten risk.

Read the full article – SNEE 2014.pdf

Hubert Fromlet

Senior Professor of International Economics, Linnaeus University

Editorial board

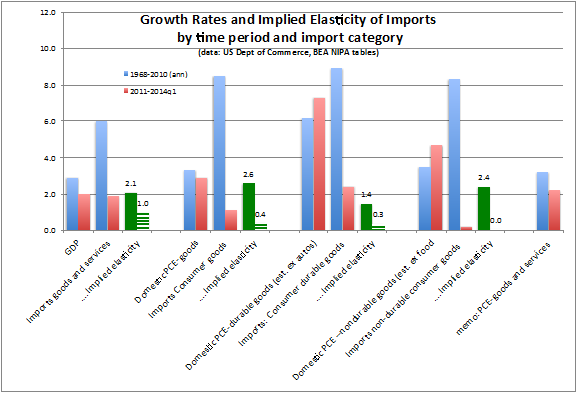

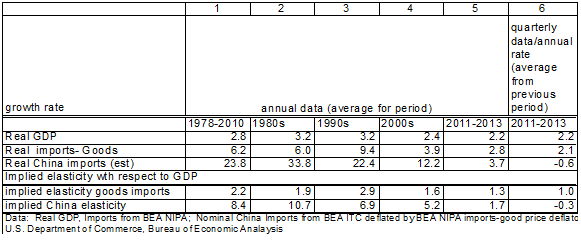

If H-M has indeed gone missing, it has implications for other countries. Foreign exporters to the US that had expected to take over from China the production of relatively cheap and easy to produce consumer goods may not experience such a robust climate for their products as was the case over the 1990s and 2000s. In fact, projections for growth in global trade are muted, with the World Trade Organization projecting global trade growth for 2014 of 4.7%. Although the WTO projection for 2015 is at the 20-year average of 5.3%, global trade growth was substantially higher than that – around 6% — in the 1990s and 2000s before the bust. [1]

If H-M has indeed gone missing, it has implications for other countries. Foreign exporters to the US that had expected to take over from China the production of relatively cheap and easy to produce consumer goods may not experience such a robust climate for their products as was the case over the 1990s and 2000s. In fact, projections for growth in global trade are muted, with the World Trade Organization projecting global trade growth for 2014 of 4.7%. Although the WTO projection for 2015 is at the 20-year average of 5.3%, global trade growth was substantially higher than that – around 6% — in the 1990s and 2000s before the bust. [1]