During summer, we have seen – and still see – quite some nervousness about the so-called BRIC countries in the emerging world – and some contagion to a couple of emerging market countries that also try to catch up, like Indonesia and Turkey. Three questions seem to be particularly interesting:

¤ Is the current nervousness about BRIC countries really motivated?

¤ Why do we have these contagion effects to several countries – to some extent similar to developments during the Asian crisis of 1997-98?

¤ Do we currently see the beginning of a real BRIC crisis which may turn much worse and which will also mean a notable downsizing of BRICS countries’ potential (trend) growth?

————————————————————————————————————————————–

BRIC is a term that has been coined in the beginning of the past decade by an economist from Goldman Sachs, a major American investment bank. BRIC –nowadays BRICS since South Africa joined the “club” a few years ago – are the initial letters of Brazil, Russia, India and China. I always considered the BRIC(S) thing mainly as a marketing instrument for asset allocation. In reality, these countries did not have enough in common to put all four eggs in one basket. Relatively good economic growth during a couple of years and a large population were simply not enough to “harmonize” analysis and investment strategies for these countries.

By the way, similar simplifications could be recognized already in the latter part of the 1990s when Eastern Europe Equity Funds and Asia Equity Funds were launched as attractive alternatives for investors. At that time, countries with different structural and institutional conditions were put in the same investment baskets, too. This proved to be wrong after some time. BRIC supporters from all over the world could have learnt from these examples.

Many experts see the main reason for the current “BRICS problems” in the expectations of – right or wrong – forthcoming cautiously rising interest rates in the traditional industrial world, especially in the U.S. Such a development could (probably) lead to (further) substantial capital outflows from BRIC countries to North America (the U.S.) and (parts of) Europe, according to the BRICS pessimists.

This explanation, however, is too fluffy. A deeper analysis of the BRICS problems is urgently needed. Are there fundamental reasons for the contagion? Or have we got a new example of overreacting financial markets?

Let’s first look at possible common characteristics of the four BRIC countries – South Africa is excluded in this context – that may have caused negative feelings about the BRICs as a group.

¤ Portfolio shifts? More financial inflows to the traditional OECD countries – at the expense of portfolio investments in emerging markets because of expected gradual, cautious monetary tightening by mainly the Fed (with the assumption that the four above-mentioned, leading emerging markets are running the highest outflow risks)

–> could partly serve as an explanation because the four above-mentioned BRIC countries represent the economically four most important emerging economies.

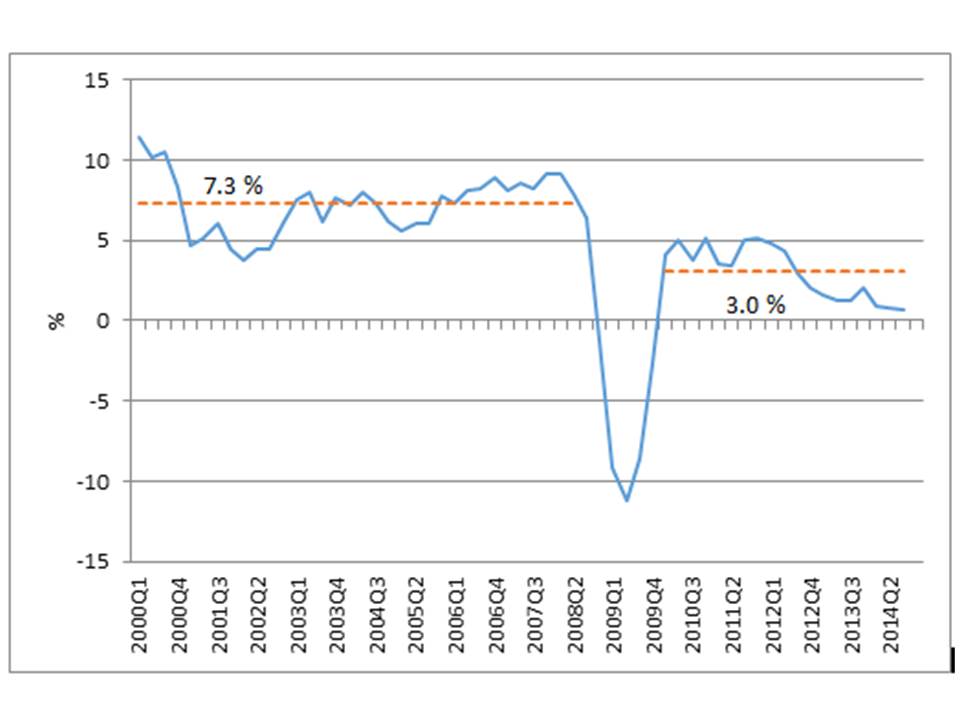

¤ Substantial slowdown in GDP growth? A rapid weakening of GDP could actually been noted in only two BRIC countries during the past year – in Russia and in India. Brazil even stands for growth improvements four quarters in a row after a couple of growth stimuli.

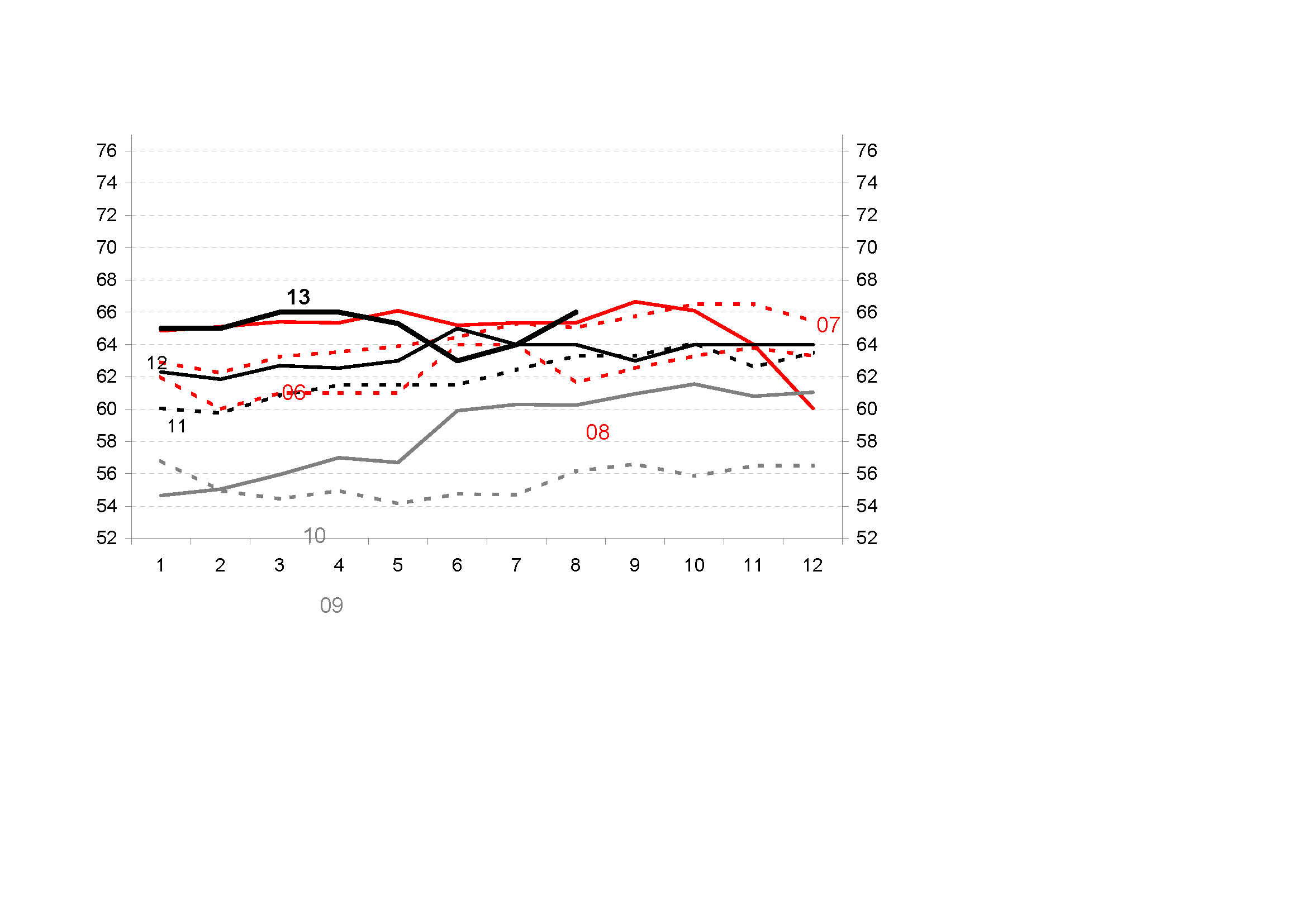

The last GDP-growth numbers for the BRIC countries look as follows:

Brazil: 2013, q2: 3.3%; 2012, q2: 0.5% –> coming down from around 9% in early 2010

Russia: 2013, q2: 1.2%; 2012, q2: 4.3% –> coming down from roughly 5% in early 2010

India: 2013, q2: 4.4%; 2012, q2: 5.3% –> compared with about

9% in early 2010

China: 2013, q2: 7.5%; 2012, q2: 7.6 –> compared with about 10% in early 2010

Obviously, GDP growth has not developed simultaneously in all BRIC countries in the past few quarters – but more visibly on trend during the past 3-4 years. This is indeed true for all BRIC countries. This development strengthens the view that more positive growth signals that currently come from the U.S., Japan and some European countries to a high extent more strongly triggered the worsening cyclical view of financial investors on BRIC countries than any other single factor. But looking at GDP-growth developments since 2010 gives also certain reasons to find structural components in the now more dampened growth outlook for BRIC. Thus, we have

–> an obvious cyclical BRIC phenomenon combined with certain negative structural components (like, for example, demand from Southern Europe) – and not a pure structural problem.

¤ Current account problems? Current account deficits are frequently used explanations for the problems of the BRICs – and the need for foreign capital inflows for financing these deficits. But only India has a (somewhat) too high deficit ratio in relation to GDP (around -4.5-5% in 2013). Brazil’s predicted deficit in the range of 3 ¼ – 3 ¾ % for 2013 is a little bit high but should not be as scaring as markets consider the entire BRIC situation. China and – probably – Russia should even continuously manage current account surpluses which takes us to the conclusion

–-> that current account problems should not really be considered as a major common problem for all the four major BRICS countries. From this point of view, the contagion effects that have been created by global financial markets, seem to be overdone. But they exist!

¤ Insufficient fiscal stability? Public debt – annual and total – is, of course, an economic indicator that all country analysts watch very carefully. In this respect, Russia and – probably – Brazil seem to have their structural fiscal conditions roughly under control. China seems to be on the safe side for the time being – at least when official numbers are analyzed (about which, unfortunately, one may have serious doubts). India finally has been affected by negative fiscal developments since a long time ago. Thus, the question is

–> why well-known fiscal conditions – which are not really bad in all four BRIC countries – suddenly should lead to general worries on global financial markets. We probably can find psychological explanations in this respect. This urges for deeper analysis.

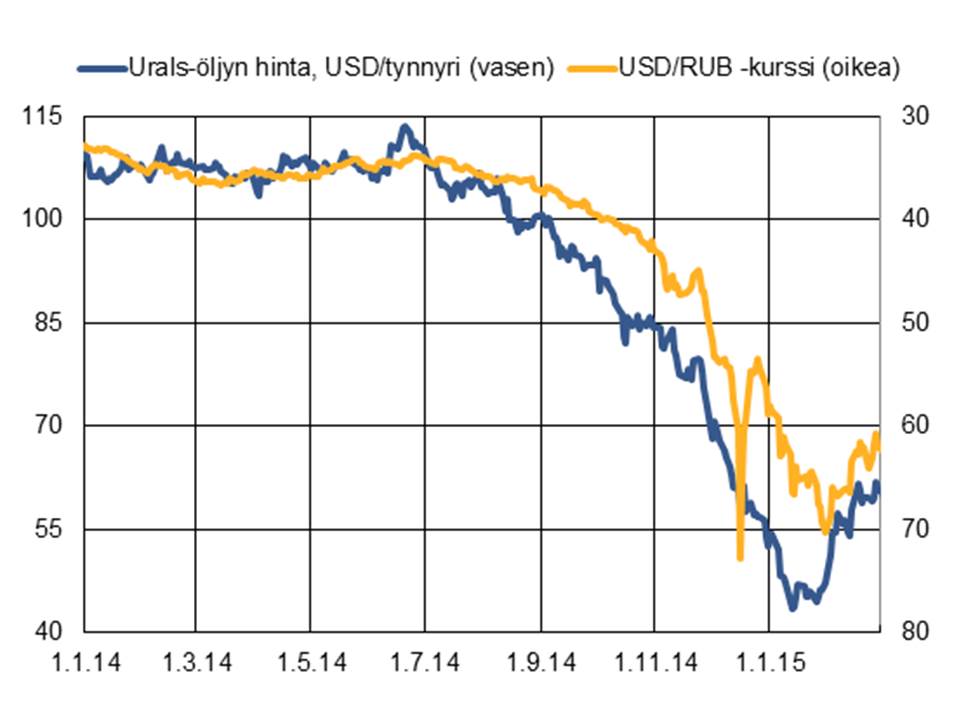

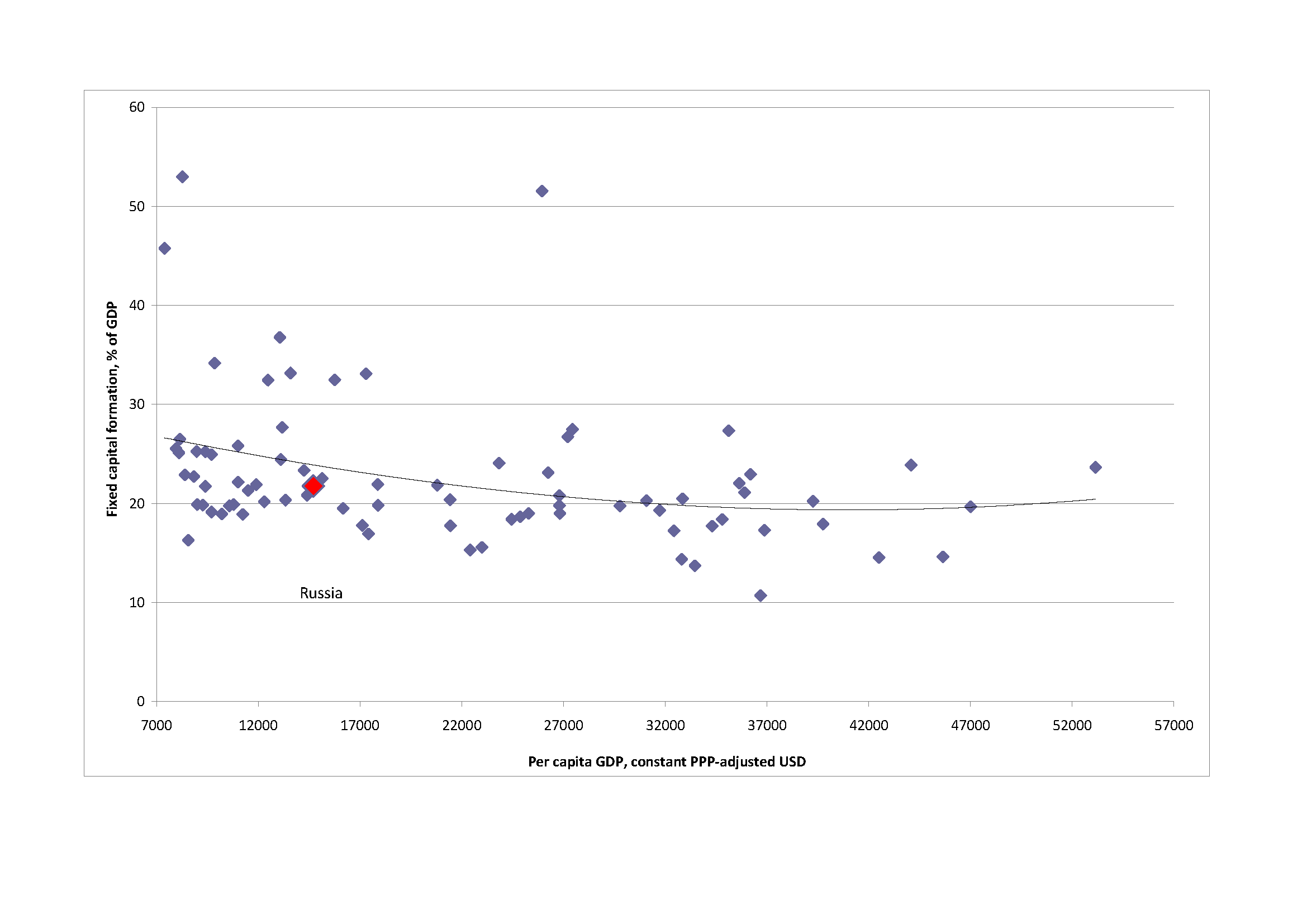

¤ Lagging structural reforms? Sure, all emerging countries have more or less burdening structural or fundamental shortcomings. What concerns Brazil, one may mention, for example, insufficient productivity gains and declining international competitiveness, lagging education and pension systems, etc. Furthermore, Brazil is nowadays increasingly competing with – currently – a more reform-minded and economically improving Mexico. Russia suffers from a significant number of institutional deficits – the financial system and support of entrepreneurship included – a too large role for the government/state in the economy and a too high dependence on the energy sector.

India, on the other hand, has more obvious fiscal problems than Brazil, Russia and China and more growth-impeding infrastructural shortcomings which are – also according to my own micro experience from these countries – much more serious than in the three other large emerging countries. The same conclusion can be made about the Indian current account deficit. Last but not least China. Nobody questions that China’s economy has proceeded substantially in the past two decades or so. But we know also that China despite all economic progress still suffers from lots of structural shortcomings particularly when it comes to microeconomic and institutional conditions – unfortunately combined with worrying transparency shortcomings.

Putting together the reflections of the above-mentioned structural thoughts means that structural shortcomings exist in all four BRIC countries

–> but without strong logical correlation for motivating sudden distortions and disappointment for the BRIC region as a whole as we have seen in the past months.

Conclusions

In my opinion, the recent negative pressure from global financial markets on the artificial BRIC group – South Africa is excluded in this analysis – should not be considered as the result of a completely consistent and logical approach. Several factors point also at psychological overshooting. Common issues for all four BRIC countries are the insufficient demand for their exports, mainly caused by weak global demand – an issue that probably is characterized by both cyclical and structural dimensions – and the expected future monetary tightening in the U.S.

I have also found that several negative macroeconomic indicators do not point at the same degree of imbalance in all four BRIC countries (if at all).Consequently, it can be singled out that certain psychological overreactions are/were in place.

For this reason, I would argue that current developments have re-set the previously overdone BRIC enthusiasm – to some extent the result of artificial financial marketing – to a more justified stance of growth expectations (without considering the issue of the middle-income trap). This should induce some reduction of previously exaggerated expectations of BRIC countries’ potential GDP growth – but probably less dramatically than described in many recent analytical pieces. Again: Almost all countries have their own characteristics. This makes it most doubtful to put several “(emerging) country eggs” in one single analytical basket.

However, occasional negative contagion effects from one country to another will most probably be inevitable in the future as well. Here we have another example that clarifies the need for more research in behavioral finance.

Hubert Fromlet

Visiting Professor of International Economics, Linnaeus University

Editorial board

Back to Start Page

![]()

![]()