How Are The Baltic Economies Doing?

Postat den 4th June, 2014, 08:24 av Mārtiņš Kazāks, Riga

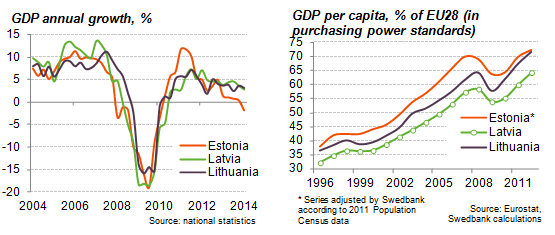

Following the sharp and deep recessions of the late 2000s when in just two years GDP collapsed by 24% in Latvia and respectively 20% and 16% in Estonia and Lithuania, the Baltic economies soon emerged as the fastest growing in the EU. Early in this decade when growth in Europe hovered just above zero, the Baltics were speeding ahead at (and sometimes above) 4-5% a year. All major imbalances were corrected – fiscal stance improved, large current account deficits erased, company and household balance sheets strengthened. As a sign of sustainability, Estonia was let into the euro area in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania is set to do it next year. Lithuanian GDP is not far from the peak of the boom years while Estonia lags by about 4% and Latvia by 8%. GDP per capita and average labour productivity in all three economies are above their boom-time peaks. Unemployment is down from 20% to about 12% in Latvia and Lithuania, and just 8.5% in Estonia. What a recovery!

The latest data is, however, less cheerful. GDP growth has slowed down, though Latvia and Lithuania still pencilled in about 3% YoY in 1Q 2014. Estonia has been doing worse – last year it hovered at just above zero and hit surprisingly weak -1.9% YoY 1Q 2014. What should we expect going forward? The quick answer is that GDP growth this year is likely to remain quite contained at about 3% in Latvia and Lithuania, i.e., some weakening and then gradually gearing up as the growth in European export markets strengthens. As for Estonia, we may see a short-lived recession this year, but growth should come back as exports benefit from a strengthening recovery in Europe and cooling off in the domestic labour market.

Why is growth expected to slow? Some of the reasons are as follows:

First, the post-recession rebound is over. In times of heightened uncertainty, consumption and investment decisions get postponed, recessions often are harsher that the necessary correction and recovery kicks in sharply when the risks of further contraction wane and confidence improves. But it only takes you that far. It is like when you push down on a spring and then let it go – the rebound is sharp, but it runs out.

Second, the Baltic economies are small open economies and their underlying growth model is that of export-driven growth. The populations are shrinking and not yet wealthy enough to drive growth via consumption for long periods without capital inflows from outside. We already saw export to be the major driver in the early stages of the post-recession recovery – with labour costs brought down by slashing wages, reducing employment and raising productivity, exports picked up by double digits year-on-year. This renewed job creation, improved labour market confidence, consumption and thereafter also investment activity. With the lowest hanging fruits of improved productivity and competitiveness already picked, and external demand in major export markets still far from its prime due to still weak European economy, export growth has been lacklustre lately. Labour market has remained strong, and household consumption last year again became the major driver of growth. But one should not be fooled – consumption is strong only as long as labour market feels confident, and it is unlikely to be the case if exports contract or are flat for an extended period. In a cartoon language, consumption is no roadrunner – it cannot run from one side of a canyon to the other. Consumption is a coyote and unless helped by a roadrunner (read – export growth), it will fall down into a canyon (read – contraction in spending). Hence, the success to revive export growth will be a crucial factor for overall economic growth going forward.

Third, the Baltic economies are small open economies with free cross-border labour market mobility and still sizeable income gaps with more advanced EU economies. To reduce the risks of emigration and demographic/social problems going forward, wages need to grow. Falling unemployment rate has been putting an increasing pressure on the wage growth and we see that average real wage growth again exceeds that of average labour productivity. This can put competitiveness and export growth at risk, and we have seen unit labour costs rising, especially in Estonia. Unless productivity growth picks up, labour market will need to cool off to safeguard export competitiveness. Given that productivity gains are difficult to generate and typically are slow to come, this means that consumption growth will need to slow down, especially in Estonia where nominal wage growth so far has been the fastest. With labour market cooling off, wage growth slowing down, and more time to raise productivity, export growth should improve again.

Fourth, the breakout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict will have a negative impact on growth. So far the impact is minor (mostly linked to certain producers of processed food) feeding through the weakness of the rouble, but the conflict is also expected to postpone some of the investment activity. As long as the conflict does not escalate further by leading to energy supply interruptions, much deeper recession in the Russian economy and significant negative spill-overs onto the West European growth, this will have only a slowing effect on the growth in the Baltics, but not push the economies into recession. If there turns out to be recession (e.g., in Estonia this year), it is for other reasons. (For a more detailed analysis on the possible impact from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, see our latest Macro Focus http://www.swedbank-research.com/english/macro_focus/2014/april/index.csp)

Why will the Baltic economies grow? Over the past 15 years growth in the Baltics has seen massive swings on the upside and downside but the overall track record is impressive – GDP per capita (similar data also for average labour productivity) has gone up from ca 36-44% of the EU average to 65-75%. Many of the low hanging fruits have been picked and catch up will become more difficult going forward, but it will not stop. There are many reasons to be optimistic such as closer integration with the EU and continually improving institutions, but one of the major reasons is that populations are still hungry for income growth and better living standards. And so far this has proven to be very important to drive agility of the Baltic economies.

Major negative risks to the outlook: externally it is the weakness of export demand (e.g., due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict), internally it is lack of productivity growth and overheating of the labour market leading to the loss of export competitiveness.

Mārtiņš Kazāks

Swedbank, Deputy Group Chief Economist and Chief Economist in Latvia

![]()

Det här inlägget postades den June 4th, 2014, 08:24 och fylls under Baltic Countries