How fast can Russia grow in the future?

October 2, 2013

Boom and bust

During the boom years of 2000-2007 Russian economy grew on average by more than 7% p.a. While the global economy also expanded vigorously, Russia’s growth was boosted further by ever-higher oil prices and productivity improvements especially in the services sector.

Russia’s rapid GDP growth meant that Russians’ average standard of living also increased during this time, and by 2008 per capita GDP (at purchasing power parities) was 34% of the corresponding level in the US from 21% in 2000. Partly this rapid growth was a rebound from the economic crisis of 1998, but growth was also helped by restructuring of the economy towards services, which were very much underdeveloped during the Soviet times and early years of the economic and political transition. Moreover, productivity growth in the services was also fast, especially in the high-skill sectors such as financial intermediation and business services, which is natural given the relatively low starting level.

However, growth during the boom years was not only driven by productivity improvements. According to a recent Discussion Paper published by the Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition (Marcel P. Timmer and Ilya B. Voskoboynikov: Is mining fuelling long-run growth in Russia? Industry productivity growth trends since 1995, BOFIT DP 19/2013, http://www.suomenpankki.fi/bofit/tutkimus/tutkimusjulkaisut/dp/Pages/dp1913.aspx) growth in the capital input has also accounted substantially to the growth in value-added. Moreover, growth in labor input has accounted for almost equally large share of value-added growth. At the same time many sectors where productivity growth has been very low, such as mining, have been able to increase their share of the economy, as they have been able to attract more capital and labour.

Lower growth in the future

In 2009 Russian economy suffered from the global financial crisis, but its post-crisis growth has been clearly slower than many expected, even though the price of oil soon returned to over $100 per barrel. While the average GDP growth between 2010 and 2012 was 4%, growth continued to decelerate. In late 2012 and early 2013 quarter-on-quarter growth was practically non-existent. While the slowdown in growth has partially been cyclical, it is also a sign of clearly lower growth in the potential output.

First, working-age population is already declining, and at the same time unemployment is very low. Officially the unemployment rate is around 5%, which in practice means full employment. Unless retirement age is increased soon, labor supply continues to decline, which will have a negative effect on future growth.

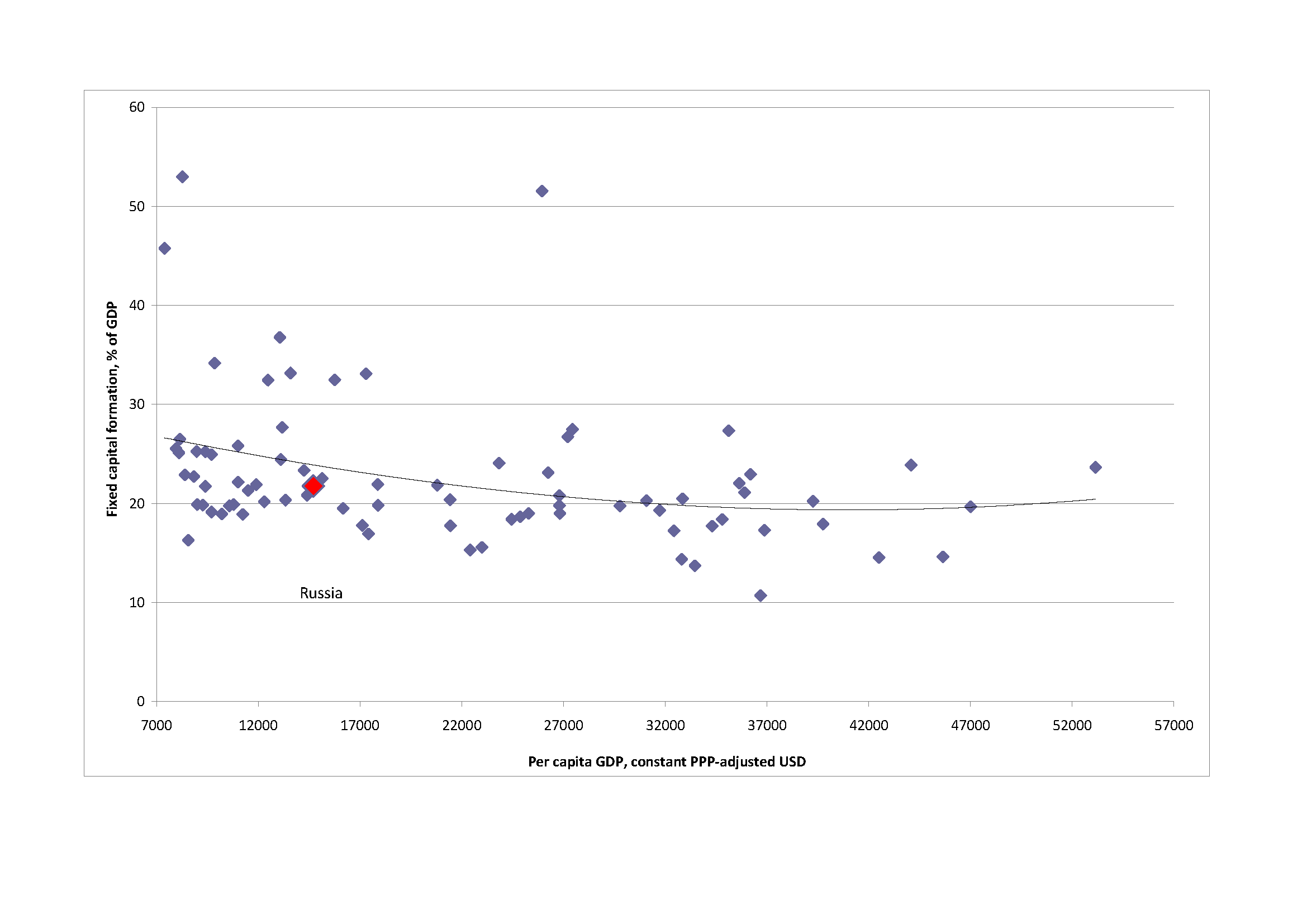

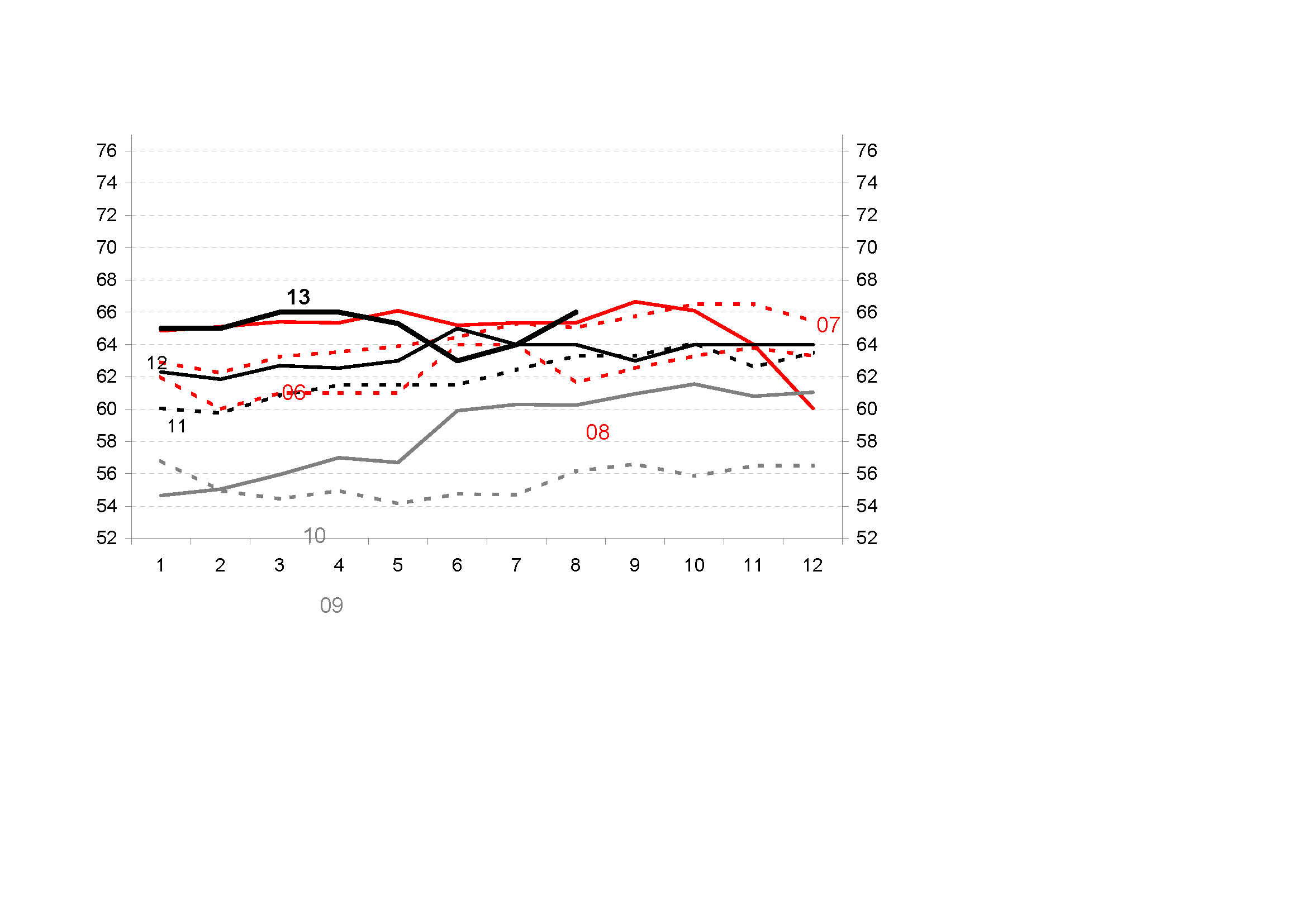

Second, investments are also declining. Between 2010 and 2012 the average share of gross fixed capital formation in GDP was 21.8%. This is below the average investment ratio of other middle-income countries (see Figure 1), many of which are currently growing faster. Moreover, during the first half of 2013 investments actually declined year-on-year, and especially large energy as well as infrastructure companies cut back their investments. At the same time capacity utilization rates are even higher than during the boom years of 2006 and 2007 (Figure 2). This tells us that Russian companies do not view their future prospects favorably, and the large capital outflows basically tell the same story. During the past quarters net capital outflows have averaged some 2.5% of GDP.

Figure 1 Share of fixed capital investments in GDP and per capita GDP (middle and high-income countries

(Click the image to zoom in)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators database

It is noteworthy that even relatively high oil prices have not been enough to boost Russia’s growth in the recent quarters. It seems that the uncertain global environment and Russia’s own well-known problems with business environment are hindering investments. It is especially noteworthy that Russian companies and investors are deeming investments into Russia lacking when taking into account the expected profits and perceived risks.

The aforementioned factors have led many analysts inside Russia and outside it to drastically reduce their estimates of Russia’s long-term growth potential. Many of the estimates seem to cluster between 2.5% and 3% p.a. While this is still quite respectable in comparison to many EU countries, it will mean substantially slower increase in incomes and delayed convergence with the OECD countries. Also, slower growth may at some point be in conflict with the many fiscal responsibilities of the public sector.

Figure 2 Capacity utilization rates in manufacturing industry

(Click the image to zoom in)

Source: Rosstat

Iikka Korhonen

Head of Bofit (Institute for Economies in Transition) at the Bank of Finland

![]()

![]()