Russia’s Economic Growth will be much Slower in the Future

April 1, 2015

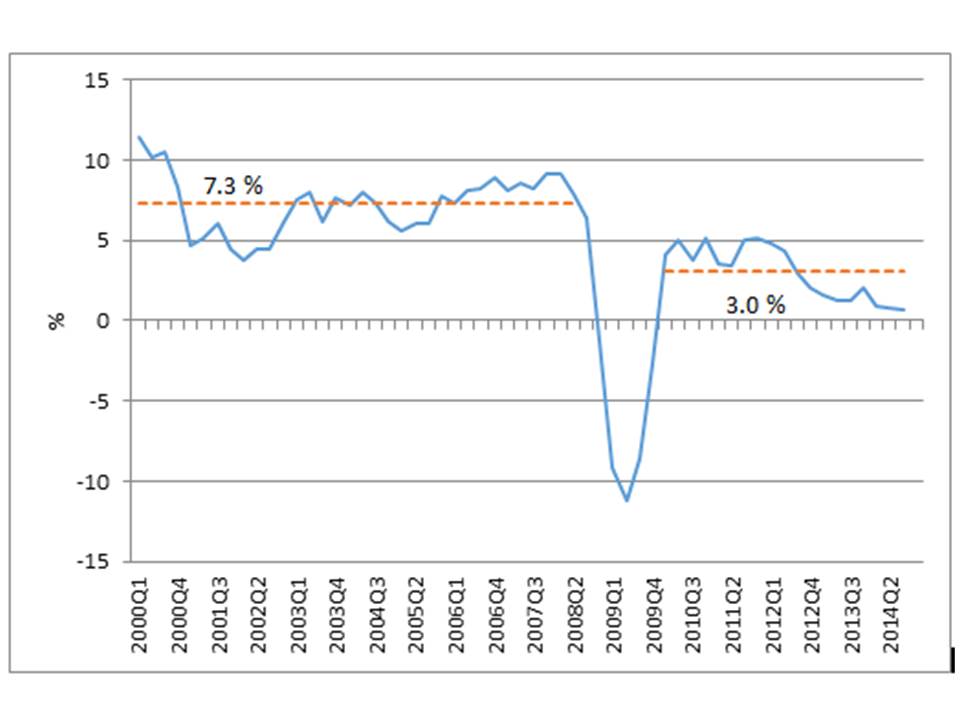

During the boom years between 2000 and 2008, Russian GDP grew by almost 7.5% per annum. This boom was caused by two interlinked factors: The global economy was growing at a very rapid pace, and the price of crude oil rose throughout the period. When the financial crisis hit major parts of the world, Russia’s economy was badly affected along with everybody else, but subsequently Russian growth has been slower than before the crisis. In addition, Russian GDP growth has decelerated almost continuously from 2011 onwards. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Russia’s GDP growth

Source: Rosstat and own calculations

There was no obvious single reason for this slowdown, but some important factors should be noted. First, Russia’s working-age population had started to decrease, which automatically slows down GDP growth, ceteris paribus. Second, Russia’s fixed capital investment remained low, between 21% and 22% of GDP after the global financial crisis. While this would not be problematic for a country like, say, Germany, Russia’s investment ratio remained much below rapidly growing emerging market countries. Third, growth in productivity had become much slower already before the global financial crisis (Voskoboynikov and Solanko, 2014). Last, the price of oil remained high, but it did not increase as it did between 2000 and 2008.

Deryugina and Ponomarenko (2014) use a large Bayesian VAR model to assess the relative importance of various macroeconomic factors in explaining the evolution of Russia’s GDP. They find that the oil price together with demand from the EU are enough to forecast and explain most of the short-run movements in Russian GDP. Rautava (2013) notes a similar dependence on the price of oil. Even more interestingly, he notes that Russia’s trend growth halved to approximately 2% after the global financial crisis.

Role of oil

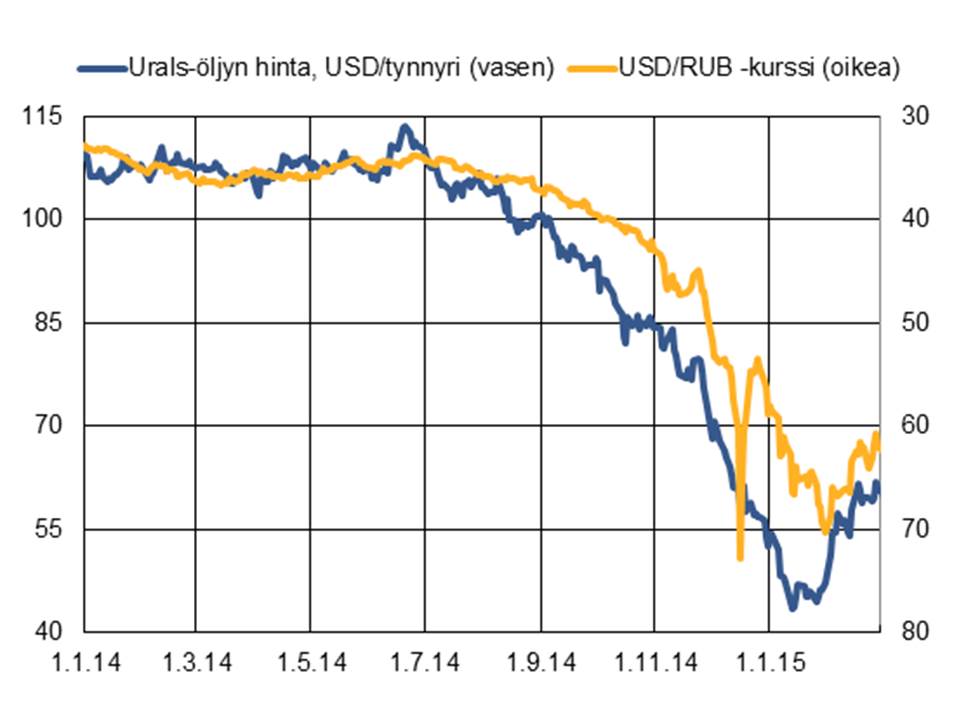

It is difficult to overstate the importance of energy prices for the Russian economy. Crude oil, oil products and natural gas brought 70% of Russia’s export revenue in 2014, and the energy sector provides the Russian Federation with more than 50% of its tax intake. Figure 2 illustrates the tight connection between the price of oil and Russia’s exchange rate.

Even after the introduction of sanctions in July, the Russian currency and financial markets remained relatively calm, but the rouble started its steep depreciation when the price of oil plummeted. Connection works in the other direction as well, of course. When the price of oil stabilized and recovered somewhat in February and March, 2015, the rouble reacted in the same direction as well.

Long-run growth slower than before

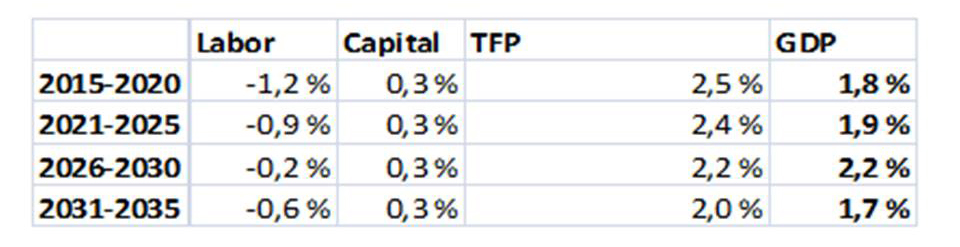

Unfortunately, Russia’s long-run growth prospects are not very rosy either, especially in comparison to the development in the recent years. We know very well about the evolution of the working-age population during the next 20 years, as almost all people coming into working-age have already been born. According to the UN prediction, Russia’s working-age population will decline from 90.7 million in 2015 to 78.7 million in 2035, which translates into -0.7% change annually on average.

Figure 2 Price of crude oil and the rouble

Even if one assumes that the capital stock will grow somewhat – say by 0.3% per annum, which is higher than recently – for the next twenty years, and total factor productivity also rises at a relatively rapid – but decelerating – pace, Russia’s GDP growth will be below 2% for the next twenty years (Table 1). This is clearly below what Russians have become used to in recent years. Also, Russia’s share of global GDP continues to decline. Moreover, Russia’s growth needs to be driven by total factor productivity. Voskoboynikov and Solanko (2014) estimate that it grew by 2.5% per annum between 1995 and 2008. Therefore, keeping Russia’s growth relatively fast at higher income levels might be difficult.

Table 1 Baseline scenario for Russian growth

References

Deryugina, Elena and Alexey Ponomarenko (2014). A large Bayesian vector autoregression model for Russia. BOFIT Discussion Paper 22/2014.

Rautava, Jouko (2013) Oil Prices, Excess Uncertainty and Trend Growth – A Forecasting Model for Russia’s Economy. Focus on European Economic Integration. Q4/13, Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

Voskoboynikov, Ilya and Laura Solanko (2014). When high growth is not enough: Rethinking Russia’s pre-crisis economic performance. BOFIT Policy Brief 6/2014.

Iikka Korhonen

Head of Bofit (Institute for Economies in Transition) at the Bank of Finland

![]()

![]()