The Baltics After the Crisis – All Back to Normal?

September 3, 2014

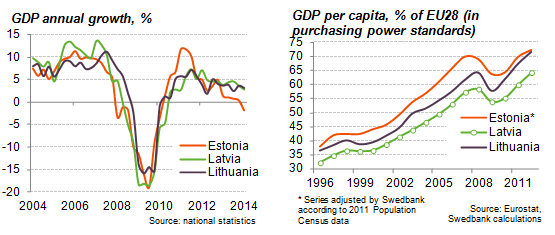

The three Baltic countries have managed a spectacular roller-coaster in the economic growth lead tables of the European Union. Having ranked among the very top in the pre-2009 period, they suffered from the most severe contraction of economic activity anywhere in Europe. But then, just as many observers got ready to include the Baltics in the long list of unsustainable ‘growth spurts’ that failed to generate sustained prosperity improvements, they came back to again top the EU in terms of growth rates in 2012. What is going on, what can be expected to happen next, and what are the lessons to draw for other parts of Europe?

In assessing the current performance of the Baltic countries it is true that the extent of post-crisis growth was at least in part a reflection of the depth of the downturn that had occurred. The crises had been so deep and left enough capacity idle to make any upturn look strong. However, it is interesting to look more at the anatomy of the recovery. It did occur in the context of strict austerity policies and a still relatively flat level of domestic demand. A key driver was exports, which grew by around 30% in 2010 and 2011 and then slowed to in 2012 around 15% for Latvia and Lithuania and 4% for Estonia. But exports have over time also gained in terms of breadth of products and markets. This was not unexpected given the drastic improvement in relative unit labor costs in response to the ‘internal devaluation’ that the Baltic countries had implemented. But it was a process that seemed to have started already before. Most likely it had to-do with a broader re-evaluation of lower cost locations in Eastern Europe as China was getting more expensive and lost some dynamism.

For the immediate future, however, it is likely that growth will flatten. The 2013 growth rates were already lower; in Estonia they dropped dramatically. Trade has in 2013 fallen in Estonia and Latvia. The one-time opportunities of bouncing back after a crisis are by definition limited. The more structural changes in the attractiveness of the Baltics as an export platform might have the potential to support further growth. But the most attractive opportunities will have come first, and it is unclear how much more potential there is.

Domestic demand is in the meantime likely to recover somewhat as growth has returned and the economic outcome has stabilized. But is not going to support the kind of growth seen in the post-crisis recovery – unless a new overheating is being engineered. The repercussions of the crisis in the Ukraine and the erosion in relations to Russia have created further headwind: some of the recent export success had gone into Russia, the Ukraine, and the broader CIS region. And there could be a negative impact on the risk assessments that some investors make about the Baltics.

What lessons to draw depends on a deeper analysis of the run-up to the crisis and the policy decisions made in the Baltics thereafter? Here is my read: The Baltics weren’t perfect but they did the best given their abilities to implement the general guidelines that they received from Brussels. This was successful in improving the business environment and preparing the ground for investment and growth. But it failed to give the Baltics a clear strategy for competing in the market for export-oriented activities; most investments went into domestic-market serving sectors. And it did nothing to counter-act the danger of moving from catching-up to overheating on the back of private sector capital inflows; this was a blind-spot in the EU’s general policy framework.

During the crisis, the Baltics impressively – but also with severe social costs – dealt with the necessary re-adjustments of balance sheets and cost levels. There successful push towards Euro-Zone membership was the well-deserved price, and is a further asset in their efforts to attract foreign investment. But it also doesn’t amount to a clear strategy that would position the Baltic countries in terms of providing distinct value for specific activities and industries/clusters. Such strategic focus will be important to move beyond the competition based on lower cost, and mount an effective strategy for competitiveness upgrading and higher productivity in line with the capacity of local firms and government agencies.

Christian Ketels

Dr. Christian Ketels, Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, Harvard Business School

![]()

![]()