Survey on China’s new economic and social reform policies

May 6, 2015

April 2015

1. Do you think that the main economic and social reforms that were set up by China’s political leaders at the Third Plenum in November 2013 can be implemented roughly successfully by 2020 – the officially announced evaluation year?

Yes: 54 % No: 46 %

2. Which three envisaged areas will be the most difficult ones to reform (ranked)?

Financial markets

Institutions

Environment

3. Where do you see the three major challenges to the reform policy come from (ranked)?

Politics

Slow moves of institutions

Lack of understanding through the whole system of decisions makers

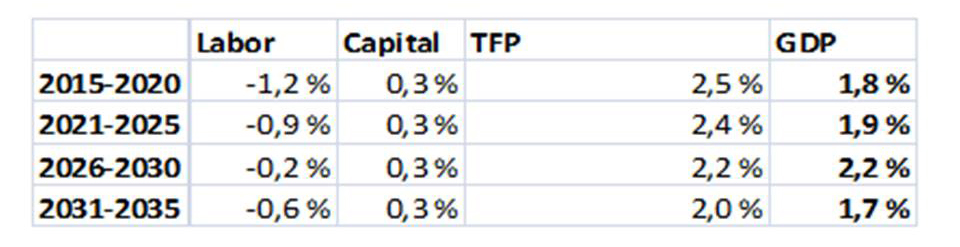

4. Considering your answers above on the importance of better quality of growth – as stressed repeatedly by the government – what kind of GDP effects do you expect in the forthcoming years

GDP-growth rates will improve until 2020

compared to current growth rates –

GDP-growth rates will stabilize at a level

of 6-7% in the years to 2020 73 %

GDP-growth rates will decline considerably

until 2020 compared to current growth rates 27 %

The quality of data will in the forthcoming years

improve: 27 % deteriorate: 9 % remain unchanged: 64 %

The transparency of data will improve

Yes: 45 % No: 55 %

5. As how important would you grade a relatively successful Chinese reform policy by 2020 for the

(scale 1-5; 5 = very important)

European economy (generally): 3.7 European corporate sector: 3.5

American economy (generally): 3.7 American corporate sector: 3.8

Asian economy outside China: 4.8 Asian corporations outside China: 4.7

Comments:

The results of our little survey should be interpreted cautiously since only 11 experts sent their answers to us. But we think that some indications are given all the same.

The respondents are really divided on the future results of the reforms plans (as it was the case one year ago).

Not very surprising: Financial markets, institutions and the environment are considered as the most difficult areas to reform or to improve.

More than 70 percent of the panel participants believe that China’s GDP growth rate will stabilize between 6 and 7 percent in the forthcoming years; this would be quite a satisfactory development with (probably) improved quality of growth at the same time. Regrettably, no major progress is expected what concerns the quality of statistics.

A relatively successful Chinese reform policy is regarded as quite important to the European and American economy – but also to the corporate sector of these two continents. In our view, the Chinese impact will be even higher beyond 2020 if Chinese reform policy were to fail. Understandably, the rest of Asia will be even more dependent on developments in China, the panelists conclude.

Hubert Fromlet

Senior Professor of International Economics, Linnaeus University

Editorial board