Hopp och kultur

2025-12-09

Idag 9 dec 2025 höll vi en paneldebatt till temat “Att skapa hopp med kulturvetenskap – bortom katastrofen” på Kulturhuset Strömmen inom ramen för Nobelveckan i Kalmar kommun. Med

- Johan Höglund, professor i engelska litteratur

- Felicia Stenberg, doktorand i engelska litteratur

- Ulrika Söderström, forskningssamordnare, Kalmar läns museum

- Gustav Wollentz, lektor i arkeologi

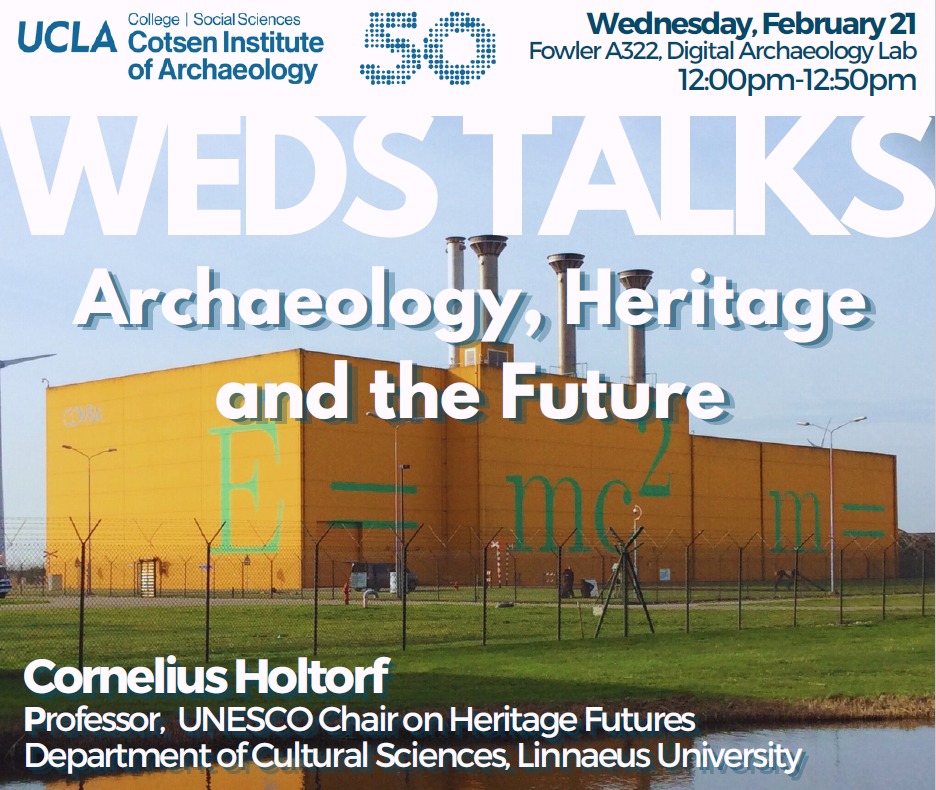

- Cornelius Holtorf, professor i arkeologi

Det blev en bra debatt mellan panelen och med publiken. Också en tjuvstart för ett nytt gemensamt projekt 2026 om Hopemaking…

Foto: Mathias Lafolie

Sammanfattning: vi lever i en tid då framtiden ofta framställs som hotfull – klimatkris, krig, oro och kollaps präglar både nyheter och populärkultur. Samtidigt finns ett växande behov av att föreställa sig något annat: att tänka och känna bortom katastrofen.

Kulturvetenskapen kan här spela en avgörande roll. Genom att undersöka våra berättelser, bilder och idéer om framtiden kan den hjälpa oss att odla hopp och handlingskraft i krisernas tid. Det är utgångspunkten för eftermiddagens samtal.

[…] The new funding for this and a number of additional smaller projects, means that the Climate Heritage Network is…

[…] Chair on Heritage Futures « Culture, cultural heritage and COP26 […]

[…] mer på Unescoprofessurens blogg http://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/?p=1061 Besök Öland 2050! […]