Claudio Pescatore: The Deep-Time Reality of Nuclear Waste

2025-08-21

Claudio Pescatore explains why high-level waste still needs shields—and memory beyond a million years:

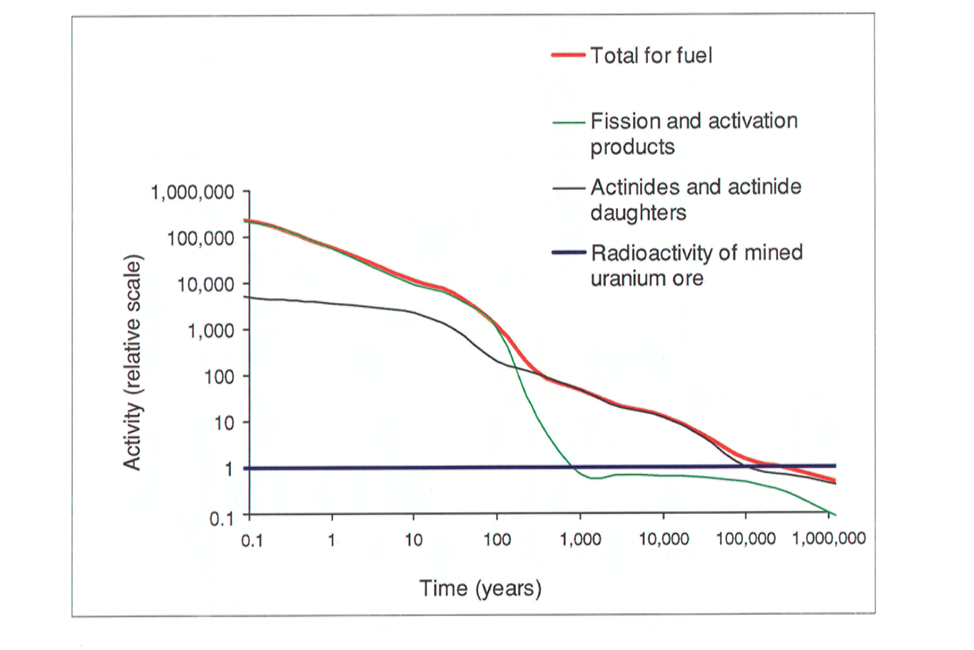

When it comes to high-level waste repositories, the old reassurance — “radioactivity falls back close to or below natural levels” — is misleading. Yes, if you total up all the radioactivity in a repository and compare it to the original ore, the sum may look modest after ten to a hundred thousand years, depending on waste type. But people (and animals) don’t meet sums. They meet things: individual containers, cores, and fragments that concentrate radioactivity. What matters—ethically and practically—is the radiation dose at the surface of each piece as time rolls on.

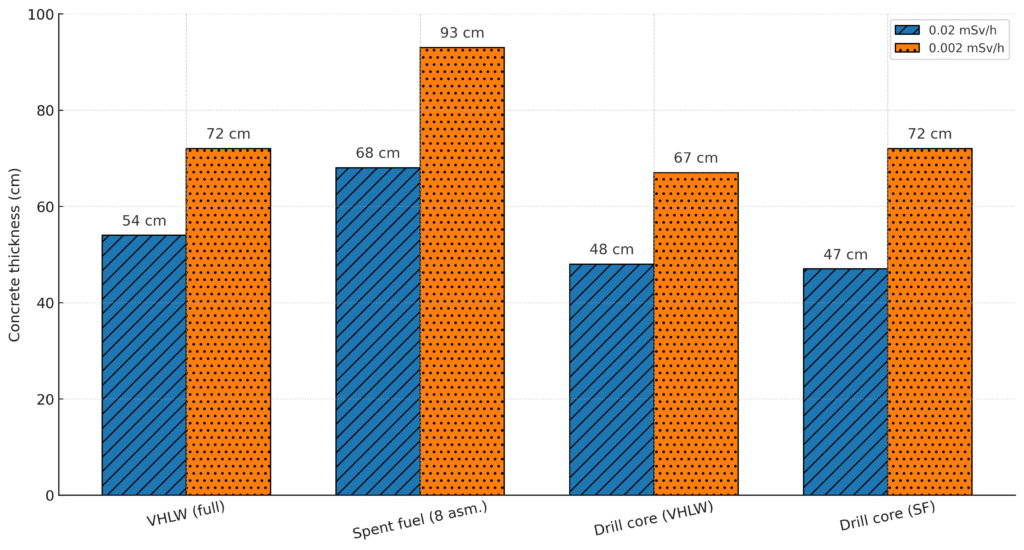

A new paper looks squarely at that reality. Rather than only computing dose, a concept for radiation specialists, it asks a tangible question: how thick must a shield be to meet modern radiation protection limit not just now, but at one million years and beyond? Using concrete as the reference, the answer comes in units anyone can picture: roughly 50–90 cm at a million years, depending on the waste and the protection target.

At one million years (and ignoring any container):

- Spent fuel (SF) requires about 67–93 cm of concrete for a representative multi-ton package

- Vitrified high-level waste (VHLW) requires about 53–72 cm of concrete for a full-size cylinder.

Beyond one million years, uranium-238 — lasting billions of years — makes the shielding requirement essentially constant: without containers, concrete thicknesses range from 7–42 cm for vitrified-waste cylinders and 62–87 cm for spent fuel.

Smaller isn’t safer. Even drill cores (say, 40 cm tall by 10 cm wide) or fragments still need shielding on the same order, because near-surface dose depends on what’s inside, not the item’s size. At a million years, unshielded drill cores still translate into about 48–67 cm of required concrete for vitrified waste and about 46–72 cm for spent fuel.

Scale matters. Numbers per item are only half the story. Program scale multiplies these requirements: for example, Sweden plans roughly 6,000 spent‑fuel canisters. In France, there will be more than 50,000 vitrified-waste cylinders.

What this means in human terms

- Heritage, not waste alone. If descendants encounter these materials—by curiosity, drilling, erosion, or chance—they won’t face a vanishing hazard but an enduring one, beyond legal timeframes and planning horizons. Our commitment to protect future people “to levels comparable to today” becomes concrete—literally—in centimeters of real shielding.

- Justice and foresight. Thinking “per item” reframes responsibility. Are we designing containers—and contingencies—that keep each piece safe, including broken pieces? The ambition is that we should.

- Design humility. Landscapes move; encounters may occur. The ethical stance is not to promise a perfect fortress forever, but to equip future people with buffers that still work: robust, intelligible, possibly maintainable shields—and the memory provisions (institutional handovers, markers, archives, time capsules) to keep that knowledge alive. Also, acknowledge that these wastes never become harmless.

So what now?

- Build for fragments. Don’t just model intact packages; assume cores, partial breaches, and erosion-revealed segments—and assign them shielding, too.

- Specify the long-lived drivers. Make a standard reporting of the deep-time isotopic loadings, because they determine both the danger and the shield.

- Design the message with the material. If safety demands 50–90 cm at a million years, our markings and archives should be designed to last—and be rediscoverable—on comparable horizons. Or that should be the ambition.

- Expand the lens. Apply similar analyses to other long-lived wastes that carry significant uranium-238 loadings.

Takeaway: this isn’t a new fear; it’s a clearer ethic. We owe the future not only sealed vaults and clever signs, but credible buffers—thicknesses you can measure with a ruler—matched to how matter behaves over time. The shield is not a metaphor; it’s a promise we can make, and keep.

Further reading

Claudio Pescatore, Beyond a million years: Robust radiation shielding for high-level waste Nukleonika, 70(3): 87-93.

https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/nuka-2025-0009 (open access)

[…] The new funding for this and a number of additional smaller projects, means that the Climate Heritage Network is…

[…] Chair on Heritage Futures « Culture, cultural heritage and COP26 […]

[…] mer på Unescoprofessurens blogg http://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/?p=1061 Besök Öland 2050! […]