Listening as an essential skill for future heritage practices

![Diana Policarpo, Ciguatera [Installation], The Soul Expanding Ocean #4 [Exhibition]. Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Ocean Space, Venice. Seen on 30.04.2022.](https://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/wp-content/blogs.dir/209/files/sites/209/2023/04/20220430170237_IMG_1923.jpg)

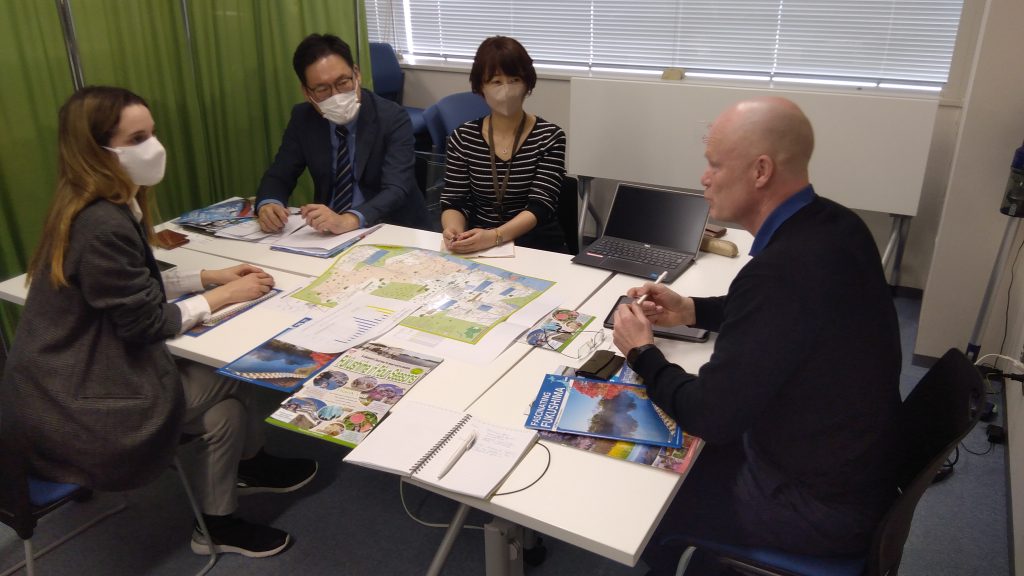

Diana Policarpo, Ciguatera [Installation], The Soul Expanding Ocean #4 [Exhibition]. Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Ocean Space, Venice. Seen on 30.04.2022.

This year’s theme of the IDMS reflects on Heritage Changes and alternative sources of knowledge for welcoming our uncertain futures. It emphasizes Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems as valuable sources for finding solutions for meeting the SDGs and encourages heritage experts and institutions to open up dialogues at all levels of society and with other sectors in order to ensure representation in decision making processes with regards to the environment.

This is a theme widely explored through the Panorama Platform within its Panorama Nature-Culture Community, which shares examples of good practices which seek to enhance the linkages between human communities and other-than-human communities and find solutions of co-existence and possibly flourishing together. Most of the explorations into these solutions are based on collaborations with Indigenous, traditional and local communities and the co-production of ecosystem management strategies, for ensuring the wellbeing of all types of communities and the conservation of heritage. When scrolling through the diverse case studies on the platform, one can come across approaches which touch upon diverse narratives which are usually woven into the “heritage for climate action” discourse: from indigenous healers engaged into actions aimed at saving tree species, to greening itineraries which lead to world heritage sites, to convincing people of the values of the conservation of their homes as an act of sustainability (just to name a few). Although all of these offer examples of action and therefore they create a sense of hopefulness, the common assumptions that seems to surface from these approaches, as well as those employed in similar actions in general, are that:

- Nature is an isolated object from ourselves, a realm to which we do not belong, and in need of our intervention in order to save it.

- Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities are inherently willing to remain as they are (or as they are imagined) and offer solutions for environmental damages produced so far.

- Cultural and Natural Heritage are static objects, which at best could be changed by bringing them into a state in which they were before (a “before” which is difficult to locate in time, although some might say “before the industrial revolution”).

This is not to say that such approaches are not useful in defining new models of interacting with our environments. Rather, these approaches touch upon the surface of the problem which lays at the heart of the current multiple crises we are experiencing. For tackling these, more powerful tools are needed which are able to decisively influence our very ways of envisioning ourselves as species within a broader context of an array of environments. Multispecies studies for example look at the multiple entanglements of livelihoods and of diverse communities of species and how these interact and influence each other, drawing also from Indigenous philosophies in this way. This might be an appropriate starting point for envisioning heritage practices as part of a management process of ecosystems and therefore bear in mind the impacts that our decisions related to heritage management have not just on humans but on other-than-humans as well.

This becomes all the more important if we are to consider the power of heritage in shaping human values and behaviors and in defining our place in the world. In this case the following question arises: what is it that we bring with ourselves from our pasts that we would like to carry with us in the future? Reflecting upon the past in this case becomes not a nostalgic reflex, but rather identifying what it is that we’ve been carrying with us as societies. And in this sense, and keeping in mind the futures we envision for ourselves and for future generations, what is it that we might perhaps shed off as it will not be useful in these envisioned futures any longer? These are relevant reflections as we must acknowledge that, despite admirable efforts to slow down the rapid changes our worlds are undergoing, these changes in one form or another will happen and therefore the best we can do is to actually prepare. This means taking precautions, of course, but it also means that our very ways of relating to change, to uncertainty, to our environments, must be steered towards acceptance and foresight equally.

As much as we like to believe it, traditional knowledge is not static either. Surely if one were to document a traditional community across decades, they will notice changes in ways of perceiving and relating to the world, unless these lived completely isolated from other human communities (but even so might be influenced by changes in the rest of the environment). Too much tokenism has been expressed by outsiders in relation to Indigenous, traditional or local communities, and therefore when entering such a domain there is a need to proceed not just ethically, but also in attempts to establish genuine relationships in order to understand the other intimately. Too often, the sounding of these communities as sources of valuable knowledge for tackling the challenges we encounter is similar to that of careless extraction of resources from the rest of the environment. The first thing to keep in mind when seeking advice in such a context could be as simple as asking ourselves if these communities want to have anything to do with our actions. For this, heritage experts need to leave behind their desire to persuade people into values and actions and rather just listen.

Perhaps it all comes down to the simple act of listening carefully, to human worlds and other-than-human worlds as well. Not for replying, not for finding solutions, but just for the sake of listening. This is an act which heritage experts will need to acquire if they want to be prepared both for the changes within our worlds, and for the changing of the heritage sector as well. After all, when imagining diverse futures, we are in a position of envisioning different ways of relating to the past as well.

Elena Maria Cautis

Elena Maria Cautis, PhD student with the Centre for Applied Heritage and the UNESCO Chair on Heritage Futures at Linnaeus University.

18 April is the International Day for Monuments and Sites, coordinated by ICOMOS. This year the theme is “Heritage Changes”.

![Diana Policarpo, Ciguatera [Installation], The Soul Expanding Ocean #4 [Exhibition]. Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Ocean Space, Venice. Seen on 30.04.2022.](https://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/wp-content/blogs.dir/209/files/sites/209/2023/04/20220430170237_IMG_1923.jpg)

[…] The new funding for this and a number of additional smaller projects, means that the Climate Heritage Network is…

[…] Chair on Heritage Futures « Culture, cultural heritage and COP26 […]

[…] mer på Unescoprofessurens blogg http://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/?p=1061 Besök Öland 2050! […]