Claudio Pescatore: Uranium and Nuclear: Humanity’s Web of Liabilities

2025-11-06

Claudio Pescatore explains why uranium’s chemical hazard is not a distant issue but a present debt — and why it will remain forever.

Not tomorrow, but today

When most people think of nuclear waste, they imagine glowing canisters buried in rock, hazards for a far-off future. The truth is different, and more unsettling. The greatest uranium problem is already with us now.

From the deserts of the American Southwest to abandoned mines in Central Asia, uranium residues contaminate soil, rivers, and aquifers. Communities live with the consequences today — kidney disease, unusable water.

Present-day scars

The Navajo Nation (U.S.) bears the legacy of Cold War uranium mining. Hundreds of abandoned mines and one out of four contaminated water-wells leave residents facing disproportionate health risks, needing endless cleanup.

Wismut (Germany), once the largest uranium mine outside the Soviet Union, has been under remediation since reunification. Billions of euros have been spent, yet groundwater plumes persist and treatment must continue indefinitely.

Mailuu-Suu (Kyrgyzstan), a former Soviet mining town, is home to dozens of unstable tailings piles above a river valley. Landslides and floods threaten to spread contamination widely.

UMTRA sites (U.S.), meant to stabilize mill tailings from past uranium production, continue to show uranium plumes exceeding drinking-water standards decades after closure.

These are not failures of engineering so much as reflections of uranium’s nature: a hazard that does not diminish on human timescales. Covers break, dams erode, pumps wear out. Each “remedy” is temporary, and each handoff pushes costs into the future.

We hardly use what we extract

Of all uranium mined for the nuclear fuel cycle, less than 0.4% has been used in reactors. The other 99.6% remains as residues — mill tailings, depleted uranium, and reprocessed uranium (see Figure 1). Its inventory by stock type is shown in Figure 1. For each ton of Uranium is spent fuel, there will also exist an additional 9 tons as Depleted Uranium or Mill-tailings uranium.

Figure 1. Distribution of humanity’s uranium by stock type. Depleted uranium (≈69.5%) and uranium mill tailings (≈19.5%) dominate the global inventory, while spent fuel (≈8.1%) and reprocessed uranium (≈2.9%) make up the remainder.

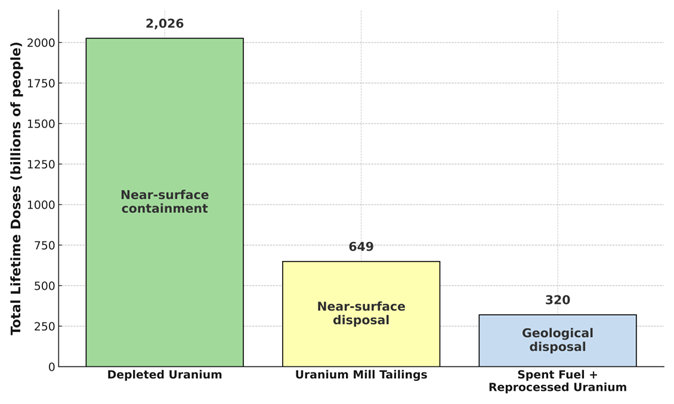

Figure 2 shows that the largest uranium stocks — DU and mill tailings — are exactly those left near the surface. In other words, the smaller share is given the world’s most advanced containment, while the larger share remains exposed. Put differently: a single metric ton of uranium represents hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of water needed for dilution, and millions of lifetime toxic doses. Multiplied by thousands of tons, the numbers are staggering.

Figure 2. A measure of the liability from managing uranium is the Total Lifetime Doses (TLD) indicator. Values associated with each stock represent the number of lifetime-equivalent chemo-toxic exposures, expressed in billions of people. As the largest stocks of uranium reside in Depleted Uranium and in Mill Tailings, there lies most of the uranium liability to the future. Yet they receive far less stringent containment.

A web of liabilities

Uranium’s hazard is not just technical. It is woven into a web of liabilities:

– Geographical liabilities: Uranium may be mined in one country, enriched in another, and its waste left in a third. Communities that never benefited from the electricity pay the price. The Navajo did not choose the bombs their ore fueled; Mailuu-Suu’s residents did not choose Soviet reactors.

– Temporal liabilities: Every cover or dam has a lifespan measured in decades or centuries. Uranium’s hazard lasts for billions of years. Each cycle of repair and neglect transfers liability to the next generation.

– Institutional liabilities: Regulators often focus on radium or radon, ignoring uranium itself. Mining laws may require closure plans but not perpetual stewardship. Health agencies emphasize chemical toxicity, while nuclear agencies emphasize radiation. No one body takes full responsibility.

The result is a system that allows uranium to slip through the cracks, its hazard passed along invisibly until it reemerges as a plume, a lawsuit, or an abandoned site.

Externalization of uranium costs

Uranium’s spread dismantles the idea of nuclear energy as “clean.” Yes, reactors emit little carbon dioxide. But the residue they generate — and the residues left by mining and enrichment — are anything but clean. Calling nuclear clean externalizes uranium’s costs onto:

– future generations, who will inherit broken dams and leaking piles;

– local communities, often Indigenous or marginalized, who live with toxic water and unsafe lands;

– other geographies, as uranium mined elsewhere, in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe and North America leaves residues that outlast states and borders.

Nuclear power may be low-carbon, but when uranium’s chemical liability is ignored, it is not low-cost, low-risk, or clean.

As an example, countries like Finland or Sweden that only have spent fuel still carry an indirect liability ten times as large in terms of Total Lifetime Doses and Dilution Liability. This stems from the additional uranium mill tailings and depleted uranium left to others to manage. Unlike spent fuel, these vast residues remain in shallow sites, piles, or surface storage — often in jurisdictions with lower environmental standards and certainly facing the endless remediation that surface storage entails.

Toward accountability: a Uranium Liability Convention

How do we begin to govern such a debt? One step is recognition: uranium is the parent hazard. It should not be masked by proxies like radium or radon.

But recognition is not enough. Uranium is traded globally, yet its liabilities are stranded locally. This calls for a Uranium Liability Convention (ULC) — a framework to:

– Map liabilities: track where uranium has been mined, processed, stored, and abandoned.

– Assign responsibility: link benefits and burdens so costs cannot be endlessly shifted.

– Set binding obligations: require durable containment, including deep disposal for depleted uranium.

– Integrate health and environment: recognize both chemical and radiological hazards.

Such a convention would not be a technical fix. It would be a moral and political acknowledgment that uranium’s hazard cannot be wished away, and that accountability must match the timescales of the debt.

What this means in human terms

– For communities now: remediation cannot be partial. The Navajo, Mailuu-Suu, Wismut, and countless others need more than fences and promises. They need durable remedies that reduce exposure and stop passing costs to their children.

– For nuclear debates: sustainability claims must account for uranium’s unresolved debt. Low-carbon is not clean when its waste contaminates forever.

– For future generations: memory and containment must last longer than institutions usually plan for. Passing the burden on is not stewardship; it is abandonment.

Takeaway

The uranium hazard is not a future scenario. It is present contamination, future inevitability, and permanent liability.

It is a web that links countries, generations, and institutions. And unless we confront it honestly — by recognizing uranium itself, containing it durably, and sharing responsibility globally — that web will only tighten.

Uranium is not just fuel or waste. It is an environmental debt. The question is whether we will keep externalizing it, or whether we will finally take responsibility for paying it down.

Further reading

– Claudio Pescatore (2025). Humanity’s Uranium Inventory: A Persistent Chemical and Ecotoxicological Liability. Energy Research & Social Science 127 (2025) 104298 in open access

Claudio Pescatore is a member of the UNESCO Chair on Heritage Futures at Linnaeus University

[…] The new funding for this and a number of additional smaller projects, means that the Climate Heritage Network is…

[…] Chair on Heritage Futures « Culture, cultural heritage and COP26 […]

[…] mer på Unescoprofessurens blogg http://blogg.lnu.se/unesco/?p=1061 Besök Öland 2050! […]