New histories for new futures

Postat den 11th January, 2026, 19:59 av Cornelius Holtorf

Historian Sandra Mass reflected in an important new book on Zukünftige Vergangenheiten (Future Pasts) on what it means, and could mean, to be writing history in the Anthropocene. This is a timely topic very relevant to the concept of ‘heritage futures,’ for it addresses ‘history futures’. By that I do not only (even mainly) mean the future of researching and teaching history, as she mostly does, but rather the significance today of composing stories of the past that enhance people’s capacity of meeting the challenges of the future (but see her discussion on p. 46-7). As I see it, the primary question is not which future pasts (i.e. descriptions of our present) future historians should be presenting but which present and future histories (i.e. accounts of the past) are most likely to benefit future presents.

This does not mean that the future and people’s future needs are predetermined and can be foreseen. But Mass agrees as well that the future is no longer entirely open either, as climate change and nuclear waste, for example, create facts that reduce future human options (p. 33, 103-4). Following Zoltán Simon, it may even be that humanity as such will be threatened in an entirely novel future taking the hit of climate change, nuclear war, and/or artificial intelligence (p. 106). What does that possible prospect mean for future history, potentially lacking significance in an altogether different reality? Could history in such a world cease to exist even without humanity to end (p. 107)?

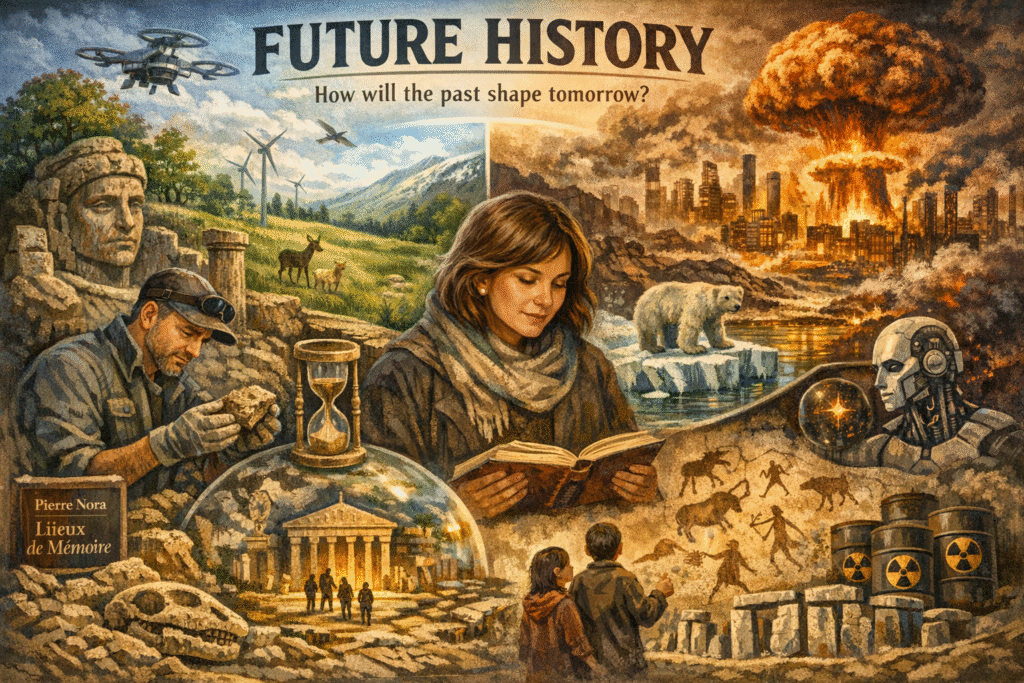

The end of history? An illustration of the present text by ChatGPT.

Sandra Mass writes particularly convincing and insightful in her extensive discussion of “More-Than-Human-History,” an emerging focus that is particularly pertinent for understanding the Anthropocene and goes far beyond existing environmental history. Such a non-anthropocentric history will be helpful for placing Homo Sapiens into a larger planetary perspective fostering much needed insights and understandings of past, present, and future realities that can push the historic disciplines beyond many past agendas that are possibly losing in significance.

In this context, what Mass missed is not only the many obvious (to me anyway) links to Archaeology and the work of archaeologists. Clearly, she is aware of the potential of archaeology (p. 35) and considers it easy to integrate archaeology and some other neighbouring disciplines into historical agendas (p. 179-80). Fine! More seriously is her omission of the significance of heritage and history culture (Geschichtskultur) for addressing the challenges of the Anthropocene.

Prominent scholars in historically oriented disciplines (including Pierre Nora, David Lowenthal, and Ian Hodder) argued that in a societal perspective, the significance of cultural heritage (and purposefully constructed sites of memory) has been superseding that of history (and living memory of the past). What will matter in future societies, I therefore suggest, is not primarily the extent to which scholarly knowledge will be able to represent important historical path dependencies during our and subsequent presents. Instead, what will matter more is the extent to which stories about the past manifested in cultural heritage relate, or will relate, to people’s lives and inform human behaviour by expressing and reinforcing particular collective identities, values, and mindsets that may or may not be in the best interest of future generations.

I argue therefore that historians, archaeologists, and others have important roles in shaping the future by giving attention to heritage futures now: the role of heritage in managing the relations between present and future societies.

Det här inlägget postades den January 11th, 2026, 19:59 och fylls under blogg